This is part 2 of Dr. Glenn Clark’s lecture on Sleep Breathing Disorders for Dental Residents of the online Master of Science in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine program at the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC.

Although the field of sleep disorders is relatively new, new scientific discoveries are helping dentists better understand the role the tongue and the jaw play in causing sleep disordered breathing and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA).

What is Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)?

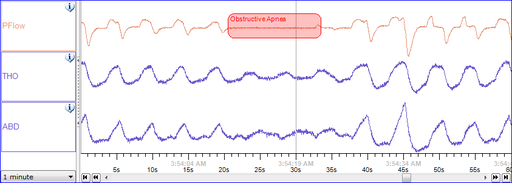

Obstructive Sleep Apnea is the episodic complete closure of the airway when the muscle tone of the body relaxes during sleep, and at the level of the throat, the human airway is composed of collapsible walls of soft tissue which can obstruct breathing during sleep. Obstructive Sleep Apnea snoring is different than primary snoring.

OSA is a type of snoring disorder where patients have a characteristic snoring pattern which consists of loud snores or short gasps that alternate with episodes of silence that usually last 20 to 30 seconds. The snoring is commonly so loud that it disturbs the sleep of bed partners or others sleeping in close proximity.

Apneic episodes characterized by cessation of breathing may be noticed by an observer and is usually of concern to a bed partner. The termination of the apneic event is often associated with loud snores and vocalizations that consist of gasps, moans, or mumblings.Like what you’re learning? Take it a step further and test your clinical diagnosis skills with USC’s Virtual Patient Simulation. Review real-life patient histories, symptoms, and imaging, conduct a medical interview and clinical exam, make a diagnosis, and create a treatment plan for virtual patients experiencing Orofacial Pain conditions.

Upon awakening, patients typically feel unrefreshed and may describe feelings of disorientation, grogginess, or mental dullness. Severe cases of OSA can be associated with cardio-respiratory insufficiency, including the morbidly obese patients with the eponymic Pickwickian syndrome or obesity-hypoventilation syndrome.1

How frequent is Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)?

For many years, the figure of 2 – 5 % of the adult population over the age of 30 has Obstructive Sleep Apnea. The Male:Female ratio for OSA is 2:1 with the gap closing after menopause. Prevalence of OSA increases into the 5th decade and then decreases for older individuals (this may be due to the occurrence of stroke and heart attacks).

Recent data suggest the above traditional figures are too low. A composite of data taken from studies out of Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Spain shows the epidemiology of Obstructive Sleep Apnea occuring 1/ 5 (20%) adults with mild OSA and 1/ 15 (7%) with at least moderate OSA.2

Sleep-Disordered Breathing Among Adults

There is some controversy regarding how many people suffer from obstructive sleep disorders. An often quoted 1993 study on the occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle age adults involving 603 randomly selected working-age adults were studied with an overnight polysomnogram.3

The authors reported 4% percent for men and 2% for women had apnea using the criteria of moderate sleepiness and an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) greater than 5 per hour. In agreement with these data is a 2009 report on the prevalence of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and snoring that used data collected in the 2005-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted by the national institutes of health on a probability sample of the USA residents.4

The study sample included 6,139 individuals over the age of 16 and was analyzed for sleep-related disease based on questionnaires and interviews. The study reported that the prevalence of sleep apnea was 4.2%, and for snoring while sleeping it was 48%.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea in the U.S.

However, the prevalence figure that claims only 4% of men have apnea is disputed by other studies. For example, a study was conducted in the on adults in the USA in 2006.5 This study used the Berlin sleep apnea questionnaire, and sampled 1,506 individuals in the USA using probability sampling.

This study found that 26% (31% of men and 21% of women) met the Berlin Questionnaire criteria indicating a high risk of OSA. The risk of OSA increased up to age 65 years. A significant number of obese individuals (57%) were at high risk for OSA. Those whose Berlin sleep apnea test scores indicated a high risk for OSA were more likely to report subjective sleep problems, a negative impact of sleep on quality of life, and a chronic medical condition than those with a lower risk.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea in the General Population

A similar study was reported in 2011, and it used a probability sample of individuals living in Iran.6 They reported on the prevalence of high risk for OSA using the Berlin sleep apnea quiz. The study collected data between 2007 and 2008, using random-cluster-sampling.

A sample of 527 adult subjects was selected from the urban region of Kermanshah, Iran, and they were aged between 20 to 87 years old. The results of this approach showed that there were 144 out of 527 subjects (27.3%) who were rated as high risk on the Berlin questionnaire. These subjects had a mean age of 48.6±16.6 years and a body mass index (BMI) of 25.1±3.3. The study also found that 261 (49.5%) of these subjects suffered from snoring.

Interestingly only 51 (10%) reported being aware of a breathing pause more than once per week during sleep. Certainly, the Berlin Questionnaire could be finding subjects at high risk, which are not aware of or do not yet have apnea, but if this data is correct then the rate of apnea may be much higher than previous studies have reported.

What are the medical consequences of untreated OSA?

Mild, occasional sleep apnea may not be important, and there is a debate about whether treatment is necessary. In contrast, untreated moderate to severe Obstructive Sleep Apnea has substantial medical consequences such as increased cardiovascular disease and cognitive deterioration.

OSA has also been associated with increased mortality. The most important and pervasive consequence of untreated OSA is an altered quality of life due to daytime fatigue, hypersomnolence, and sleep fragmentation.

The most obvious medical consequence of untreated OSA is daytime sleepiness or Hypersomnia. This means excessive sleepiness is a typical presenting complaint. The sleepiness usually is most evident when the patient is in a relaxing situation, such as when sitting, reading, or watching television. Inability to control the sleepiness can be evident in group meetings or while attending movies, theater performances, or concerts. With extreme sleepiness, the patient may fall asleep while actively conversing, eating, walking, or driving.

What is non-obstructive or Central Sleep Apnea?

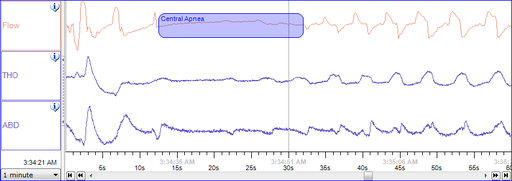

Central Sleep Apnea (CSA) is the failure to try to breathe and it occurs when the brain’s respiratory control center temporarily shuts down during sleep. Unlike Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) where the cessation is not due to an airway collapse. Upon arousal the patient begins breathing again.

In Cheyne-Stokes respiration, the brain’s respiratory control centers are imbalanced during sleep. Blood levels of carbon dioxide and the neurological feedback mechanism that monitors them do not react quickly enough to maintain an even respiratory rate, with the entire system cycling between apnea and hyperpnea, even during wakefulness.

The sleeper stops breathing and then starts again. There is no effort made to breathe during the pause in breathing; there are no chest movements and no struggling. After the episode of apnea, breathing may be faster (hyperpnea) for some time, a compensatory mechanism to blow off retained waste gases and absorb more oxygen.

While sleeping, a healthy individual is “at rest” as far as the cardiovascular workload is concerned. Breathing is regular in a healthy person during sleep, and oxygen levels and carbon dioxide levels in the bloodstream stay fairly constant. The respiratory drive is so strong that even conscious efforts to hold one’s breath do not overcome it. Any sudden drop in oxygen or excess of carbon dioxide (even if tiny) strongly stimulates the brain’s respiratory centers to breathe.

In central sleep apnea, the basic neurological controls for breathing rate malfunction and fail to give the signal to inhale, causing the individual to miss one or more cycles of breathing. If the pause in breathing is long enough, the percentage of oxygen in the circulation will drop to a lower than normal level (hypoxia), and the concentration of carbon dioxide will build to a higher than normal level (hypercapnia). In turn, these conditions of hypoxia and hypercapnia will trigger additional effects on the body, such as cell damage in the brain and endothelium, which can lead to a cognitive deficit and cardiovascular disease.

Online Dental Education: Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine

Do you want to deliver appropriate and safe care to your growing and ageing dental patients? Consider enrolling in our online, competency-based Master of Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine degree program.

References:

- Schmidt-Nowara WW. Cardiovascular consequences of sleep apnea. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research, 1990, 345:377-85

- Young et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med; 2002;165:1217-1239.

- Young T; Palta M; Dempsey J; Skatrud J; Weber S; Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. New England Journal of Medicine, 1993, 328:1230-5.

- Ram S, Seirawan H, Kumar SK, Clark GT. Prevalence and impact of sleep disorders and sleep habits in the United States. Sleep Breath. 2010 Feb;14(1):63-70.

- Hiestand DM, Britz P, Goldman M, Phillips B. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in the US population: Results from the national sleep foundation sleep in America 2005 poll. Chest. 2006 Sep;130(3):780-6.

- Khazaie H, Najafi F, Rezaei L, Tahmasian M, Sepehry AA, Herth FJ. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in the general population. Arch Iran Med. 2011 Sep;14(5):335-8.