Secondary Masticatory Muscle Spasm

Occasionally the jaw closers or jaw openers can develop a continuous strong spastic activity which if sustained for a long period of time, will actually produce contracture with substantial shortening of the muscle. Often this activity is secondary to another acute disease process (trauma or infection), although it can also be seen as a primary idiopathic dystonic process.

Proposed Mechanism

There are several conditions which might produce a secondary masticatory muscle spasm, including radiation of the facial tissues, spasms in association with multiple sclerosis, scleroderma, progressive supranuclear palsy, amyotrophic sclerosis, and vascular abnormalities. If the spasm is unilateral the clinician must consider hemi-masticatory spasm and focal dystonia. Often patients with spasm have a reduced opening and the clinical challenge is to determine how much of the reduced opening is due to muscle contracture and how much is due to active contraction or some other cause. [1], [2], [3]

Treatment

Certainly the approach to secondary spasm is to identify the cause if possible. For example, if the spasm is due to a traumatic injury of the temporomandibular joint, then treatment of the pain and inflammation in the joint and using an anti-spasmotic agent to suppress the motor reaction until healing occurs would be the best approach. [4]

For those spastic conditions that are not acute, self-limiting problems once local or CNS pathologies are ruled out, one approach is to use BoNT-A injections to suppress the activity. Several case reports describe BoNT-A use in patients with long-standing spasms of the jaw. [5] BoNT-A has been used to manage secondary trismus due to radiation of the facial tissues. [6] It has also been reported to be successful in managing trismus in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis who exhibited spastic contraction of the jaw. [7]

Like what you’re learning? Test your diagnosis skills with USC’s Virtual Patient Simulation. Review real-life patient histories, conduct medical interviews and exams, make a diagnosis, and create a treatment plan for patients experiencing orofacial pain.

Hemi-facial Spasm

Episodic hyperkinetic spastic contractions can affect the unilateral facial muscles. It will start with an intermittent periorbital twitching, usually of the inferior orbicularis oculi muscle. Over months to years this abnormality can progress to involve half of the face and the platysma muscle.

The muscles of mastication are not involved as this is a disorder of cranial nerve VII. Sometimes these twitching movements may progress to a sustained, chronic contraction of the involved facial muscles. [8]

When the muscles innervated by the facial nerve undergo a sudden, unilateral, synchronous contraction, this is called hemi-facial spasm. These spastic actions may be brief or may persist as a tonic contraction of several seconds’ duration and may occur many times a day. The main problem with this disorder is social embarrassment, but if the spastic contractions are strong, they may also cause pain.

Hemi-facial Treatments

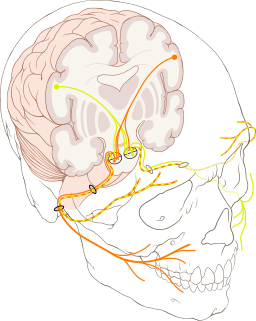

The hemi-facial spasm could be secondary to a compression to the facial nerve at the root zone, local demyelination, ephaptic transmission of impulses or hyperexcitability of the facial motor nucleus due to irritation from peripheral lesion of the nerve. [9]

It may be primary (mainly attributed to vascular compressions of the seventh cranial nerve in the posterior fossa) or secondary to facial nerve or brain stem damage. [10]

The condition might be treated with medications, botulinum toxin and surgery.

1. Oral Medications

The efficacy of oral medications in hemi-facial spasm is often transient and the drugs most commonly used are anticonvulsants (such as carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine), anticholinergics, baclofen, and clonazepam. [11], [12], [13] Gabapentin for the treatment of hemi-facial spasm has been reported in several open-label trials to have moderate success. [14]

2. Botulinum Neurotoxin (Botox) Injections

The standard medical management for HFS is botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) injections, which provides low-risk but limited symptomatic relief. [15] A review of the literature on botulinum toxin treatment in hemi-facial spasm showed that there have been numerous open-label studies and a few double-blind placebo-controlled studies with high success. [16]

Adverse effects include dry eyes, ptosis, eyelid and facial weakness, diplopia, and excessive tearing. Overall these effects are transient and no serious long-lasting effects have been reported. [17]

3. Microvascular Decompression

Microvascular decompression (MVP) is an effective curative method for almost all the patients affected with primary HFS. [18] The most common vessel causing compression of the facial nerve is the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. This vessel must be sharply dissected free from the arachnoid and mobilized laterally away from the nerve so that a Teflon implant can be placed.

In cases of atypical hemi-facial spasm, the pathological vascular entity is almost always located rostral to the nerve or between the seventh and eighth nerves. [19] MVP surgery does have a recurrence rate of up to 20% and complications include aggravation of preexisting hearing loss and mild facial weakness. [20]

Hemi-masticatory Spasm

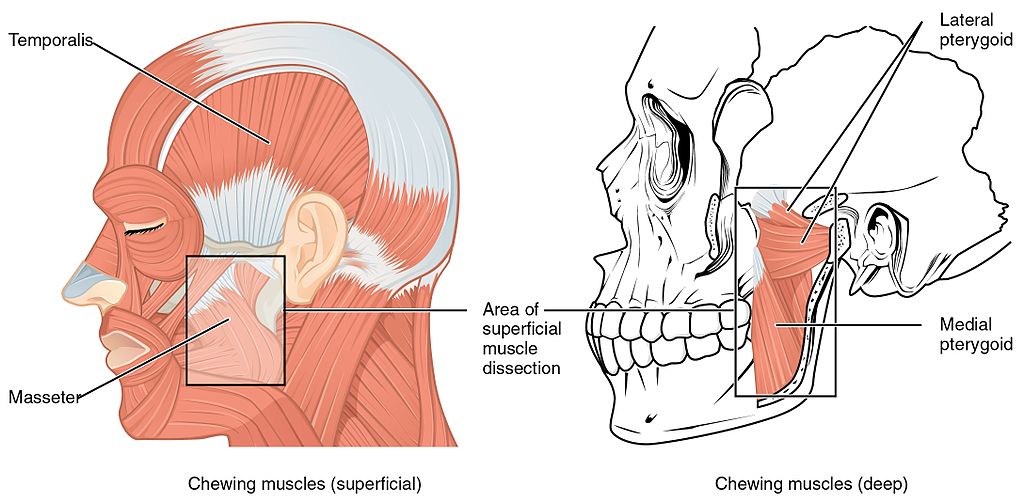

An unusual analog to the disorder of hemi-facial spasm is called hemi-masticatory spasm (HMS). The latter condition has characteristics (unilateral episodic, short lasting spastic contractions), which are virtually identical to the former, with the only difference being that hemi-masticatory spasm is essentially a spastic contraction of the masseter and temporalis muscles on one side of the face. [21] It presents as an intermittent temporalis or masseter contraction, which increases rapidly becoming severe & often painful.

Proposed Mechanism

Since this is a disorder of the motor branch of the fifth cranial nerve, the muscles of facial expression are spared. If severe, it may move from an episodic event to a sustained, chronic contraction of the involved jaw muscles. It is also likely that this condition involves the medial pterygoid, in most cases, but this is not clearly documented.

The clinical and neurophysiological findings in a case of hemi-masticatory spasm (HMS) in a single patient followed during a 14 year period after initial diagnosis showed that the clinical symptoms remained unchanged throughout the period of observation. [22]

The use of surface electromyography demonstrated irregular bursts of motor unit potentials in a patient with hemi-masticatory spasm and masseter muscle hypertrophy, even with a normal muscle biopsy. These results indicated that the contraction was related with ectopic discharges of the trigeminal nerve. [23]

Hemi-masticatory Spasm Treatment

Since the mechanisms for hemimasticatory spasm remain unclear, an efficient treatment strategy still needs to be developed, however, there are reports of management with BoNT-A and surgical approaches.

1. BoNT-A Injections

The first successful use of BoNT-A for hemi-masticatory spasm was reported on a single case of hemi-masticatory spasm. [24] HMS may have a peripheral origin, with dysfunctional contractions of the masseter muscle, hence the application of botulinum toxin injections into the affected muscle reduces the spasms. [25]

2. Surgery

A surgical technique of microvascular decompression of the trigeminal root has been used to separate the superior cerebellar artery and the motor branch of the trigeminal nerve root. To assure separation, pieces of soft wadding are interposed between the nerve and the vessel. [26], [27] If the spasms are produced by a vascular compression, a MVD surgical is a logical approach, however, control studies with large samples are needed before this technique is widely accepted as first line for HMS. [28]

Related Reading: Surgical Management for Oromandibular Dystonia

Online Postgraduate Dental Degrees in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine

Do you want to deliver appropriate and safe care to your growing and aging dental patients? Consider enrolling in our online, competency-based certificate or master’s program in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine.

References

[1] Van der Geer, S., Kamstra, J., Roodenburg, J., Van Leeuwen, M., Reintsema, H., Langendijk, J., & Dijkstra, P. (2016). Predictors for trismus in patients receiving radiotherapy. Acta Oncologica., 55(11), 1318-1323.

[2] Danisi, F., & Guidi, E. (2018). Characterization and Treatment of Unilateral Facial Muscle Spasm in Linear Scleroderma: A Case Report. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements., 8, 531.

[3] Refaee, E., Rosenstengel, C., Baldauf, J., Pillich, D., Matthes, M., & Schroeder, H. (2018). Microvascular Decompression for Patients With Hemifacial Spasm Associated With Common Trunk Anomaly of the Cerebellar Arteries-Case Study and Review of Literature. Operative Neurosurgery., 14(2), 121-127.

[4] Ram S, Kumar SK, Clark GT. Using oral medications, infusions and injections for differential diagnosis of orofacial pain. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2006 Aug;34(8):645-54.

[5] Ward, A., Molenaers, G., Colosimo, C., & Berardelli, A. (2006). Clinical value of botulinum toxin in neurological indications. European Journal of Neurology., 13 Suppl 4, 20-26.

[6] Hartl, D., Cohen, M., Juliéron, M., Marandas, P., Janot, F., & Bourhis, J. (2008). Botulinum toxin for radiation-induced facial pain and trismus. Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery., 138(4), 459-463.

[7] Winterholler MG, Heckmann JG, Hecht M, Erbguth FJ. Recurrent trismus and stridor in an ALS patient: successful treatment with botulinum toxin. Neurology. 2002 Feb 12;58(3):502-3.

[8] Padilla, M., Utsman, R., Brenes, MJ. Hemifacial Spasm: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Journal of California Dental Association. July 2017. Vol 45(7):361-4.

[9] Chaudhry, N., Srivastava, A., & Joshi, L. (2015). Hemifacial spasm: The past, present and future. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 356(1-2), 27-31.

[10] Abbruzzese, G., Berardelli, A., & Defazio. (2011). Hemifacial spasm. Handb Clin Neurol, 100, 675-680.

[11] Kemp, L., & Reich, S. (2004). Hemifacial Spasm. Current Treatment Options in Neurology, 6(3), 175-179.

[12] Liu, J., Zhang, Q., Lian, Z., Chen, H., Shi, X., Feng, M., Zhou, D. (2017). Painful tonic spasm in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: Prevalence, clinical implications and treatment options. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 17, 99-102.

[13] Rosenstengel, C., Matthes, M., Baldauf, J., Fleck, S., & Schroeder, H. (2012). Hemifacial spasm: Conservative and surgical treatment options. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International.,109(41), 667-673.

[14] Daniele O, Caravaglios G, Marchini C, Mucchiut L, Capus P, Natale E. Gabapentin in the treatment of hemifacial spasm. Acta Neurol Scand2001; 104:110–12.

[15] Lu, A., Yeung, J., Gerrard, J., Michaelides, E., Sekula, R., & Bulsara, K. (2014). Hemifacial spasm and neurovascular compression. TheScientificWorld., 2014, 349319.

[16] Jost WH, Kohl A. Botulinum toxin: evidence-based medicine criteria in blephraospasm and hemifacial spasm. J Neurol 2001; 248(Suppl.):21–4.

[17] Ramirez-Castaneda J, Jankovic J. Long-term efficacy, safety, and side effect profile of botulinum toxin in dystonia: a 20-year follow-up. Toxicon: Off J Int Soc Toxinol. 2014;90:344–8

[18] Sindou, M., & Mercier, P. (2018). Microvascular decompression for hemifacial spasm: Outcome on spasm and complications. A review. Neurochirurgie, Neurochirurgie , 2018.

[19] McLaughlin MR, Jannetta PJ, Clyde BL et al. Microvascular decompression of cranial nerves: lessons learned after 4400 operations. J Neurosurg 1999;90(1):1-8.

[20] Bigder, M., & Kaufmann, A. (2016). Failed microvascular decompression surgery for hemifacial spasm due to persistent neurovascular compression: An analysis of reoperations. Journal of Neurosurgery., 124(1), 90-95.

[21] Sun, H., Wei, Z., Wang, Y., Liu, C., Chen, M., & Diao, Y. (2016). Microvascular Decompression for Hemimasticatory Spasm: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurgery.,90, 703.e5-703.e10.

[22] Esteban A, Traba A, Prieto J, Grandas F. Long term follow up of a hemimasticatory spasm. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2002 Jan;105(1):67-72.

[23] Kim, Jin-Hyuck, Han, Seok-Won, Kim, Yun Joong, Kim, Jooyong, Oh, Mi-Suh, Ma, Hyeo-Il, & Lee, Byung-Chul. (2009). A case of painful hemimasticatory spasm with masseter muscle hypertrophy responsive to botulinum toxin. Journal of Movement Disorders., 2(2), 95-97.

[24] Auger RG, Litchy WJ, Cascino TL, Ahlskog JE. Hemimasticatory spasm: clinical and electrophysiologic observations. Neurology 1992 Dec;42(12):2263-6.

[25] Mir, P., Gilio, F., Edwards, M., Inghilleri, M., Bhatia, K., Rothwell, J., & Quinn, N. (2006). Alteration of central motor excitability in a patient with hemimasticatory spasm after treatment with botulinum toxin injections. Movement Disorders: Official Journal of the Movement Disorder Society., 21(1), 73-78.

[26] Dou, N., Zhong, J., Zhou, Q., Zhu, J., Wang, Y., & Li, S. (2014). Microvascular decompression of trigeminal nerve root for treatment of a patient with hemimasticatory spasm. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 25(3), 916-918.

[27] Yan, Ke-Kun, Wei, Jian-Bo, Lin, Wen, Zhang, Yue-Hui, Zhang, Ming, & Li, Mi. (2017). Hemimasticatory Spasm with a Single Venous Compression Treated with Microvascular Decompression of the Trigeminal Motor Rootlet. World Neurosurgery., 104, 1050.e19-1050.e22.

[28] Wang, Y., Dou, N., Zhou, Q., Jiao, W., Zhu, J., Zhong, J., & Li, S. (2013). Treatment of hemimasticatory spasm with microvascular decompression. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 24(5), 1753-1755.