There are many diseases such as Xerostomia and Salivary Gland Hypofunction, radiation therapy in the head and neck area, and medications that cause dry mouth. In this article, we present several treatment options for older patients experiencing dry mouth.

Sections

- Mouth Moisteners

- Salivary Stimulators

- Toothpastes

- Topicals

- Prescription Dry Mouth Medications

- Non-pharmacologic Interventions

- Cost Effectiveness of Treatment

Mouth Moisteners

Several mouth moisteners in the form of salivary substitutes or artificial saliva are available as rinses, aerosols, toothpastes, mouthwashes, lozenges, or chewing gums in the U.S. and worldwide, Table 3 [58], [59], [73], [74].

The principal idea of these salivary substitutes is to provide a long-lasting coating of the oral soft tissues. But sprays, liquids, or gels may need to be applied frequently throughout the day (at least 3–4 times a day) depending on their adherence and/or lasting abilities.

Lozenges or pastilles may provide a more discreet and socially acceptable means of adding moisture to the mouth since their usage maybe be better hidden. However, one needs to be aware of hidden sugars in some of these products [73], [74].

Most of the currently available preparations to moisten the mouth contain either carboxymethylcellulose or mucins although preparations based on hydroxyethylcellulose, polyglycerylmethacrylate, hydroxyprophylmethylcellulose, glycerol, canola oil, olive oil, and linseed extract are also reported to be useful [73].

Sugar-free chewing gums of various types, sweetened with sugar substitutes, xylitol or sorbitol, can be used by patients during waking hours. These chewing gums stimulate salivary production by topical gustatory or masticatory action [25], [73].

There is no evidence that gum is better or worse than saliva substitutes, probably because gums are effective only if there is remaining salivary functional tissue [73], [74]. However, chewing gums can be problematic for older adults, especially those who wear removable appliances [45] or have arthritis effecting the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Lozenges or pastilles containing Xylitol that dissolve on the tongue or are adherent to the buccal surface of the tooth and are not to be chewed may give better comfort for these cases, with less likelihood of adhering to the denture component or aggravating TM joints.

Like what you’re learning? Download a brochure for our Geriatric Dentistry Master Program certificate or master’s degree program.

Salivary Stimulators for Dry Mouth

| Preparation | Products | Active Ingredients |

|---|---|---|

| Mouth rinses/washes | Biotene Dry Mouth Oral Rinse (GlaxoSmithKline) Colgate® Dry Mouth Relief Fluoride Mouthwash (Colgate) Spray Oral Rinse (Spry Dental Defense System)* Oasis Moisturizing Mouth Wash (Oasis Consumer Healthcare) Act Total Care Dry Mouth Soothing Mouthwash (Chattem, Inc.) | Glycerin, xylitol, sorbitol, propylene glycol, hydroxyethyl cellulose Not available Xylitol, glycerin Glycerin, water, sorbitol Glycerin, sorbitol, xylitol, propylene glycol |

| Patches | Oramoist dry mouth Patches (Quantum) | Xylitol, polyvinylpyrrolidone, carbomer homopolymer, hydroxypropyl cellulose, lysozyme, lactoferrin |

| Spray | Water/Glycerine Spray MOI-STIR (Pendopharm, Pharmascience Inc.) Biotene Moisturizing Mouth Spray (GlaxoSmithKline) Oralube (Perrigo Australia) Spry Oral Mist (Spry Dental Defense System) Oasis Moisturizing Mouth Spray (Oasis Consumer Healthcare) CVS Dry Mouth Spray (CVS Pharmacy)/Rite Aid Dry Mouth Spray (Rite Aid Pharmacy) | Glycerin Carboxymethylcellulose sodium, glycerin Glycerin, xylitol, hydrogenated castor oil Methyl hydroxybenzoate, sorbitol Glycerin, Xylitol, Sorbitol Glycerin, sorbitol, poloxamer 338, PEG 60, hydrogenated castor oil Xylitol, aloe vera, lactoferrin, lyzozyme, glucoxidase, amylase, amylogucosidase, peptizyme |

| Gel | GC Dry Mouth Gel (GC America Inc.) Dentist dispensed Biotene Oral Balance Moisturizing Gel (GlaxoSmithKline) Orajel Dry Mouth Gel (Church & Dwight, Inc.) | Not available Glycerin, sorbitol, xylitol, carbomer, hydroxyethyl cellulose Glycerin |

| Toothpaste | Biotene Dry Mouth Fluoride Toothpaste (GlaxoSmithKline) Spry toothpaste (Spry Dental Defense System) | Glycerin, sorbitol Glycerin, xylitol, sorbitol |

| Salivary substitute solution | Saliva Substitute (Roxane laboratories) Prescription | Purified water, sorbitol, sodium carboxymethylcellulose, etc. |

Oral Moisturizers & Salivary Substitutes for Dry Mouth

| E/M Code | HPI (# elements) | ROS (# systems) | PFSH | Exam (# elements) | MDM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99212 | 1-3 | 0 | 0 | 1-5 | straightforward |

| 99213 | 1-3 | 1 | 0 | ≥ 6 | low |

| 99214 | ≥ 4 | 2 | 1 | ≥ 9 | moderate |

Toothpastes, fluoride as treatment

Toothpastes designed for the treatment of dry mouth may subjectively improve symptoms but do not improve salivary gland function [73]. Many people with dry mouth prefer non-foaming gel-type toothpastes that are less irritating than foaming toothpastes, which have surfactants in them that can prove to be problematic [25].

Since reduced salivary flow can have detrimental effects on the dentition, aggressive caries prevention and management play vital roles in maintaining the dentition for patients with dry mouth [32]. Regular dental visits and a meticulous oral hygiene regimen should be encouraged [32].

Both professionally applied varnish (2.26% fluoride or 5% Sodium fluoride varnish) and prescription-strength, home-use topical fluorides (0.5% fluoride or 1.1% neutral sodium fluoride gel/paste, 0.09% fluoride mouth rinse) have been recommended as effective and beneficial measures for caries prevention in older adults [32], [75].

Effectiveness of Topicals

Although some topical agents, by patient report, do seem to cause a lessening of dry mouth symptoms, thus improving the quality of life for some, there is no strong scientific evidence that any topical treatment is effective for relieving the sensation of dry mouth [74] and recent literature indicates that no one topical agent is better than another [73].

Patient preference appears to play a significant role in the acceptance and attribution of efficacy [32], [74]. The make-up of most lubricants and salivary substitutes do not duplicate the compounds found in saliva and therefore lack its protective effects, although some of them contain fluoride and electrolytes to prevent demineralization [32], [59].

Any preparation containing substances problematic for causing caries or tissue discomfort such as sugar, acid and/or alcohol should be avoided in patients with dry mouth [32].

Prescription Dry Mouth Medications

In cases when topical therapy cannot provide adequate relief of dry mouth symptoms or cannot control the complications of dry mouth, prescription-strength systemic medication in the form of sialagogues such as pilocarpine and cevimeline, orally administered parasympathetic agonists of the acetylcholine muscarinic M3 receptors, may be considered.

US Food and Administration approved these parasympathetic agonists to increase salivary secretion in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome (pilocarpine and cevimeline) and head and neck cancer patient with radiation-induced salivary gland hypofunction (pilocarpine only) [25], [32], [58], [63], [65], [70], [73].

These sialagogues cannot increase the function of salivary glands that are completely destroyed, but they can enhance the function when there is residual glandular tissue.

Pilocarpine

The optimal dosage of pilocarpine 5–7.5 mg three to four times daily or 10 mg 3 times daily is generally well tolerated [32], [69], [70]. Pilocarpine (SALAGEN; MGI Pharma, Bloomington, USA) should be prescribed for at least 8–12 weeks to see if there is a positive response and if long-term use would be planned due to the presence of residual salivary gland tissue that has become functional as a result of the medication [49], [70].

Cevimeline

Cevimeline (EVOXAC; Daiichi-Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan) 30 mg taken 3–4 times daily, increased salivary flow, and improved subjective and objective symptoms of patients with dry mouth and is also well tolerated by patients [32], [69], [70].

Sialagogues need to be administered long term, basically life-long since the observed clinical improvements in salivary gland hypofunction diminish after cessation of sialagogues.

Side Effects of Sialogogues

The side effects of these medications include but are not limited to sweating, increased urgency or frequency of urination, lacrimal and nasal secretion, and joint pain. Both medications, but this is true more so for pilocarpine, are contraindicated in patients with narrow angle glaucoma, acute iritis, uncontrolled asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), kidney stones, gall stones, and heart or liver disease. Both medications can cause dehydration as well. Hence, sialagogues must be given with a high rate of caution in our older adult population.

Another systemic sialagogue of interest is Bethanechol HCL with promising results in patients with radiation therapy-induced hyposalivation. However, further studies are needed to determine the dose, frequency of use, long-term efficacy, and safety for the use of Bethanechol [69], [70], [73].

Non-pharmacologic Interventions

Non-pharmacologic interventions for dry mouth include electrostimulation of the salivary glands with hand-held battery operated devices or removable intraoral devices [49], [69], [70], [73], [76]; manual and electro acupuncture [49], [69], [70], [73], [77]; hyperbaric oxygen therapy [72], [78] and application of low level laser therapy [79]. There is however little or insufficient evidence in the literature in definitive support of these interventions in the management of dry mouth [20], [72], [73].

Immunologically active agents such as interferon alpha, corticosteroids, hydroxychlorquine and other immunosuppressants such as cyclophosphamide and thalidomide have been studied for the management of dry mouth by suppressing the glandular damage from immunologically medicated diseases such as Sjogren’s syndrome and others such as sarcoidosis, HCV and HIV infection related salivary gland diseases [58].

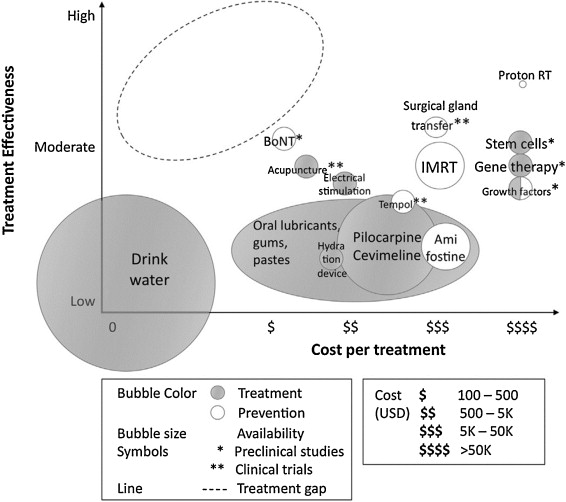

Cost Effectiveness of Treatment

Given the myriad of choices for the treatment of dry mouth, it is easy for a practitioner to be unsure as to what to recommend to a patient who has clinical signs with or without symptoms.

A cost-effective study examining the various treatments that are currently available or in development for this condition when it occurs as an outcome of head and neck cancer therapy, was mounted by Saportas et al. Her group indicated that the most effective and attractive way to address dry mouth in these patients is by protecting the salivary glands from radiation damage in the first place [49].

To do so, changes to the conventional therapy techniques previously used must be employed. Several solutions that meet this objective are available and have demonstrated moderate effectiveness.

For example, newer radiation techniques including not only Intensity-modulated RT (IMRT), but also Intensity modulated Proton Radiation Therapy (IMPRT), which uses protons instead of X-rays. When IMPRT is employed, reduced findings of hyposalivary function from 80% down to 25–40% have been reported [80], [81].

Another protective action would be to institute the use of radioprotective drugs such as Amifostine, which has been approved for the treatment of salivary hypofunction. However, this drug does have significant negative effects such as nausea and vomiting, and its use during IMRT has been indicated as possibly unnecessary since the major salivary glands are being spared in this type of therapy, unlike in conventional radiation therapy [82].

Surgical procedures, including salivary gland transfer to an area outside of the radiation field (e.g., transfer of the submandibular gland to the submental space), have been shown to spare the gland and its function [83].

Hydration devices [84] are also available as one of the current palliative treatments for radiation-induced xerostomia in addition to the administration of sialagogues, acupuncture, saliva substitutes, and electrical stimulation of salivary secretion.

Emerging preventive treatment solutions include systemic administration of growth factors such as insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1) or keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) [85], [86] administration of botulinum toxin (BoNT) [87], another radioprotective drug called tempol [88] and the regeneration of the salivary gland tissue by gene therapy or by transplantation to the salivary gland of bioengineered salivary gland germ cells [89].

Even with all of these existing and emerging therapies for radiation-induced salivary hypofunction there is a large treatment gap, and the most efficacious treatment with the most cost-effective ratio is still not available [49].

Solving this treatment gap will not only serve the needs of the patients with radiation-induced salivary gland hypofunction, but also will help the majority of patients who are more likely to have dry mouth from more frequently seen conditions such as medication-usage.

Conclusions

When it comes to the treatment of dry mouth conditions, either objective or subjective, there are no easy answers as to the best course of action for a specific individual.

As previously noted, there are many conditions that can cause dry mouth. While most of the cited studies have examined the most difficult cases of dry mouth, that is, those that are a result of treatment for head and neck cancer, there are many individuals who demonstrate dry mouth from far less grievous circumstances.

Taking a thorough history in an attempt to discover the contributor to and/or cause of the signs and/or symptoms and based on those findings, attempting to select the most appropriate intervention is the critical role of the practitioner. Additional factors such as patient comfort, motivation, access to the various treatments, and cost will also play a role in the selection of a successful therapy.

It is important to recall that water is an essential component for life [90]. Begin by educating the patient about possible causes of dry mouth. An analysis of fluid intake (e.g., a daily fluid diary) may be a good place to start and may also be the most practical, cost-effective, and efficient treatment with the best risk-benefit ratio.

Postgraduate Geriatric Dentistry

Are you looking for improved ways to diagnose, treat, and manage the oral healthcare of older patients? Explore our online master’s and certificate program in Geriatric Dentistry.

Conflict of Interest

Authors have neither affiliation nor financial conflict of interest with any organization or company producing the oral care products discussed and mentioned in this article.

About the Authors

The original article, “Dry mouth: A critical topic for older adult patients,” was authored by Phuu Han, Piedad Suarez-Durall, and Roseann Mulligan, Director Geriatric Dentistry Master and Certificate programs at the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, and was originally published by Elsevier in the Journal of Prosthodontic Research.

References

[20.] S. Furness, G. Bryan, R. McMillan, S. Birchenough, H.V. Worthington

Interventions for the management of dry mouth: non-pharmacological interventions

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 9 (2013), CD009603s

[25] C. Scully

Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth

Oral Dis, 9 (2003), pp. 165-176

[32.] J.M. Plemons, I. Al-Hashimi, C.L. Marek, American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs

Managing xerostomia and salivary gland hypofunction: executive summary of a report from the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs

45. J.Y. Wick

Xerostomia: causes and treatment

Consult Pharm, 22 (2007), pp. 985-992

[49.] L.S. Sasportas, D.N. Hosford, M.A. Sodini, D.J. Waters, E.A. Zambricki, J.K. Barral, et al.

Cost-effectiveness landscape analysis of treatments addressing xerostomia in patients receiving head and neck radiation therapy

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 116 (2013), pp. e37-e51

[58] S.R. Porter, C. Scully, A.M. Hegarty

An update of the etiology and management of xerostomia

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 97 (2004), pp. 28-46

[59] Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co.

Search for drugs that may cause dry mouth

(2001, November)

[63] T.O. Närhi, J.H. Meurman, A. Ainamo

Xerostomia and hyposalivation: causes, consequences and treatment in the elderly

Drugs Aging, 15 (1999), pp. 103-116

[65] Y. Peri, N. Agmon-Levin, E. Theodor, Y. Shoenfeld

Sjögren’s syndrome, the old and the new

Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol, 26 (2012), pp. 105-117

[69.] S.B. Jensen, A.M. Pedersen, A. Vissink, E. Andersen, C.G. Brown, A.N. Davies, et al.

A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: prevalence, severity and impact on quality of life

Support Care Cancer, 18 (2010), pp. 1039-1060

[70.] T.L. Lovelace, N.F. Fox, A.J. Sood, S.A. Nguyen, T.A. Day

Management of radiotherapy-induced salivary hypofunction and consequent xerostomia in patients with oral or head and neck cancer: meta-analysis and literature review

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 117 (2014), pp. 595-607

[72.] W.L. Kenney, P. Chiu

Influence of age on thirst and fluid intake

Med Sci Sports Exerc, 33 (2001), pp. 1524-1532

[73.] A. Wolff, P.C. Fox, S. Porter, Y.T. Konttinen

Established and novel approaches for the management of hyposalivation and xerostomia

Curr Pharm Des, 18 (2012), pp. 5515-5521

[74.] S. Furness, H.V. Worthington, G. Bryan, S. Birchenough, R. McMillan

Interventions for the management of dry mouth: topical therapies

Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 12 (2011) CD008934

[75.] R.J. Weyant, S.L. Tracy, T.T. Anselmo, E.D. Beltrán-Aguilar, K.J. Donly, W.A. Frese, et al.

Topical fluoride for caries prevention: executive summary of the updated clinical recommendations and supporting systematic review

J Am Dent Assoc, 144 (2013), pp. 1279-1291

[76.] R.K. Wong, J.L. James, S. Sagar, G. Wyatt, P.F. Nguyen-Tân, A.K. Singh, et al.

Phase 2 results from Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Study 0537: a phase 2/3 study comparing acupuncture-like transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation versus pilocarpine in treating early radiation-induced xerostomia

Cancer, 118 (2012), pp. 4244-4252

[77.] J.H. Cho, W.K. Chung, W. Kang, S.M. Choi, C.K. Cho, C.G. Son

Manual acupuncture improved quality of life in cancer patients with radiation-induced xerostomia

J Altern Complement Med, 14 (2008), pp. 523-526

[78.] D.N. Teguh, P.C. Levendag, I. Noever, P. Voet, H. van der Est, P. van Rooij, et al.

Early hyperbaric oxygen therapy for reducing radiotherapy side effects: early results of a randomized trial in oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal cancer

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 75 (2009), pp. 711-716

[79.] B. Lončar, M.M. Stipetić, M. Baričević, D. Risović

The effect of low-level laser therapy on salivary glands in patients with xerostomia

Photomed Laser Surg, 29 (2011), pp. 171-175

[80.] M.K. Kam, S.F. Leung, B. Zee, R.M. Chau, J.J. Suen, F. Mo, et al.

Prospective randomized study of intensity-modulated radiotherapy on salivary gland function in early-stage nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients

J Clin Oncol, 25 (2007), pp. 4873-4879

[81.] C.M. Nutting, J.P. Morden, K.J. Harrington, T.G. Urbano, S.A. Bhide, C. Clark, et al.

Parotid-sparing intensity modulated versus conventional radiotherapy in head and neck cancer (PARSPORT): a phase 3 multicentre randomized controlled trial

Lancet Oncol, 12 (2011), pp. 127-136

[82.] A. Eisbruch

Amifostine in the treatment of head and neck cancer: intravenous administration, subcutaneous administration, or none of the above

J Clin Oncol, 29 (2011), pp. 119-121

[83.] H. Seikaly, N. Jha, T. McGaw, L. Coulter, R. Liu, D. Oldring

Submandibular gland transfer: a new method of preventing radiation-induced xerostomia

Laryngoscope, 111 (2001), pp. 347-352

[84.] P.M. Frost, P.J. Shirlaw, J.D. Walter, S.J. Challacombe

Patient preferences in a preliminary study comparing an intra-oral lubricating device with the usual dry mouth lubricating methods

Br Dent J, 193 (2002), pp. 403-408

[85.] I.M. Lombaert, J.F. Brunsting, P.K. Wierenga, H.H. Kampinga, G. de Haan, R.P. Coppes

Keratinocyte growth factor prevents radiation damage to salivary glands by expansion of the stem/progenitor pool

Stem Cells, 26 (2008), pp. 2595-2601

[86.] K.H. Limesand, J.L. Avila, K. Victory, H.H. Chang, Y.J. Shin, O. Grundmann, et al.

Insulin-like growth factor-1 preserves salivary gland function after fractionated radiation

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 78 (2010), pp. 579-586

[87.] A. Teymoortash, F. Müller, J. Juricko, M. Bieker, R. Mandic, D. Librizzi, et al.

Botulinum toxin prevents radiotherapy-induced salivary gland damage

Oral Oncol, 45 (2009), pp. 737-739

[88.]

J.M. Vitolo, A.P. Cotrim, A.L. Sowers, A. Russo, R.B. Wellner, S.R. Pillemer, et al.

The stable nitroxide tempol facilitates salivary gland protection during head and neck irradiation in a mouse model

Clin Cancer Res, 10 (2004), pp. 1807-1812

[89.] M. Ogawa, M. Oshima, A. Imamura, Y. Sekine, K. Ishida, K. Yamashita, et al.

Functional salivary gland regeneration by transplantation of a bioengineered organ germ

Nat Commun, 4 (2013), p. 2498

[90.] S.M. Kleiner

Water: an essential but overlooked nutrient

J Am Diet Assoc, 99 (1999), pp. 200-206