What if it’s possible to regrow those pearly whites, perhaps at a fraction of the cost ?[1]. That is a compelling question, especially considering that tooth loss can result from various causes, including tooth agenesis, a congenital condition in which one or more teeth fail to develop, as well as from various other health-related issues. [2]. Studies have shown aggregated data linking chronic systemic health conditions and multiple health-risk behaviors to increased rates of tooth loss [3]. As a major public health concern, tooth loss affects physical function, psychological well-being, and social participation. Tooth loss impacts nutrition, speech, confidence, and quality of life. Addressing this issue is a goal of both clinical and public health dentistry.

However, another concern related to research and innovation is how public interest and enthusiasm can intersect with the clinical and ethical decision-making process. Recent breakthroughs in tooth regeneration have captured public attention. When such developments are reported in headlines or news articles aimed at general audiences, the research may be misinterpreted, leading some to believe, for example, that biological tooth replacement is already feasible or widely available.

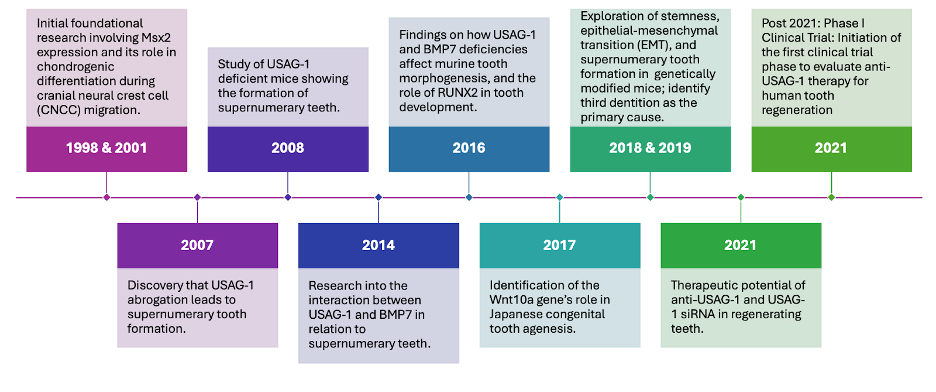

Recently, scientific interest has surged around USAG-1 (Uterine Sensitization Associated Gene-1), a gene that functions as a negative regulator of the BMP (Bone Morphogenetic Protein) signaling pathway, a pathway essential for tooth development [2]. By inhibiting USAG-1, researchers have demonstrated the ability to stimulate tooth regeneration in animal models, suggesting the potential to induce a third set of teeth in adult humans. Figure 1 illustrates the research timeline supporting USAG-1, which shows promise as a potential therapeutic target for tooth regeneration. It is important to note that this innovation is not yet ready for clinical use, which may lead to misunderstandings or contribute to an infodemic, as some individuals could be misled into believing it is an immediate solution for tooth loss. Figure 1 highlights the timelines for bringing innovations to trials or practice [5].

Figure 1.

Progression From Basic Science to Clinical Application of Regenerative Dentistry

Note. The timeline of the therapeutic potential of regenerative oral health adapted from Ravi et al. (2023) depicts the potential for application in 2021.

This breakthrough could represent a shift from prosthetic tooth replacement toward true biological regeneration. The implications are profound: regenerating whole teeth with roots, enamel, and pulp could provide more natural and long-lasting solutions than current alternatives, such as implants or dentures [2]. However, scientific potential is not the same as clinical readiness, and this distinction is not always clear to the public. Media headlines often omit important details about the early research and how many years of development, testing, and approval remain [1]. USAG-1 research began in animal models around 2018 and entered early human clinical trials in 2024. Even under optimal conditions, widespread availability is unlikely before 2030. Like other biomedical innovations, USAG-1 therapy must undergo rigorous preclinical stages over 2-5 years and clinical trials over 5–10 years, followed by years of regulatory reviews.

Like what you’re learning? Consider enrolling in the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC’s online, competency-based certificate or master’s program in Community Oral Health.

The Risk of Misunderstanding

Despite these timelines, oversimplified or sensational media reports can shape public understanding. Some patients may delay evidence-based treatment while waiting for breakthroughs they believe are imminent. Yet, the consequences of untreated tooth loss and psychosocial factors may continue. In some cases, patients may become emotionally or financially invested in future treatments that may never materialize or be accessible to a limited population segment. Perhaps most concerning is when patients decline evidence-based treatments while waiting for regenerative options, make financial decisions based on anticipated availability of treatments, lose trust in dental providers when promised innovations never materialize, or experience psychological distress when hoped-for solutions remain perpetually on the horizon.

Responsible communication about USAG-1 and similar innovations requires providing explicit research timeline context, using accessibility indicators that signal research stage, addressing community-specific information needs, and centering current care options. The ethical obligation may be the responsibility of several stakeholders to build capacity for communities to understand scientific information actively.

It is important to note the feasibility of clinical use, which could result in misconceptions, as the public may be misled into perceiving the readiness of health solutions. From an ethical standpoint, healthcare professionals have a responsibility to communicate the current limitations of emerging technologies clearly and accurately. Therefore, health and clinical decision-making must be guided by scientific evidence and ethical considerations related to transparency, patient autonomy, and patient values [6]. Clinicians should be transparent when uncertain about an innovation, avoiding speculation. Admitting knowledge limits upholds ethics, builds trust, manages expectations, and reinforces their role as supportive, reliable sources amid widespread misinformation.

The Role of Informing

Communities vary widely in how they understand and interpret scientific research. Medical jargon, lack of access to credible sources, and social media amplification contribute to confusion [4]. These challenges are especially acute in underserved populations, who are already more likely to suffer from tooth loss and have fewer resources to evaluate complex health claims. In this context, ethical communication is about simplification and empowerment. Practitioners and educators must build community capacity to understand research, distinguish between developmental stages, and assess the credibility of information. This is especially urgent when emerging technologies are unlikely to be distributed or pose inequitable opportunities in the early stages of rollout or trials.

Ethical Responsibilities of Health Professionals

Dental educators, providers, and researchers should examine the basis for ethical responsibility to distinguish clearly between novel ideas and evidence-based care. Ethical communication about oral health innovations like USAG-1 should include the following in addition to professional judgment [7]:

1. Contextualizing research timelines

2. Using accessible language and visuals to explain novel research

3. Correcting misinformation and encouraging questioning

4. Developing collaborative programs for community health workers and dental professionals to train community members.

Conclusion

It is noble and worthy to pique public interest in innovation, but with ethical guidance. The science behind USAG-1 may one day revolutionize the treatment of tooth loss. But until clinical efficacy, safety, and accessibility are fully established, ethical communication must take precedence over hype, encourage questions, and maintain a focus on evidence-based care. Health innovation, at its best, will create improvements, not compromises or confusion.

Earn an Online Postgraduate Degree in Community Oral Health

Do you like learning about a variety of issues while focused on the unique needs of community health dental programs? Consider enrolling in the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC’s online, competency-based certificate or master’s program in Community Oral Health.

References

[1] Discover. Regrowing teeth is on the horizon and may represent the future of dentistry. (2025, Jan. 24). https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/regrowing-teeth-is-on-the-horizon-and-may-represent-the-future-of-dentistry

[2]. A. Murashima-Suginami et al., “Anti-USAG-1 therapy for tooth regeneration through enhanced BMP signaling,” Science advances, vol. 7, no. 7, 2021.

[3] S. G. Alzahrani, K. Rijhwani, and W. Sabbah, “Health‐risk behaviours co‐occur among adults with tooth loss,” International journal of dental hygiene, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 857–862, 2024.

[4] I. J. Borges do Nascimento et al., “Infodemics and health misinformation: a systematic review of reviews,” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, vol. 100, no. 9, pp. 544–561, 2022.

[5] V. Ravi et al., “Advances in tooth agenesis and tooth regeneration,” Regenerative therapy, vol. 22, pp. 160–168, 2023.

[6] Ratnani, S. Fatima, M. M. Abid, Z. Surani, and S. Surani, “Evidence-Based Medicine: History, Review, Criticisms, and Pitfalls,” Curēus (Palo Alto, CA), vol. 15, no. 2, pp. e35266–e35266, 2023.

[7] D. Cardoso et al., “The effectiveness of an evidence-based practice (Ebp) educational program on undergraduate nursing students’ ebp knowledge and skills: A cluster randomized control trial,” International journal of environmental research and public health, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2021.