Introduction: The Evolution Toward Competency-Based Assessment

The landscape of medical education has undergone a profound transformation over the past two decades, shifting from time-based training models to competency-based medical education (CBME). This paradigm shift reflects the recognition that competency-based medical education “focuses on the skills and progression of learning of an individual, promoting greater learner-centeredness and potentially allowing greater flexibility in the time required for training” (Carraccio et al. 2002). Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) were developed in 2005 by ten Cate to provide the opportunity for frequent, time-efficient, feedback-oriented and workplace-based assessment in the course of daily clinical workflow, serving as a critical bridge between broad competency frameworks and daily clinical practice (ten Cate 2005).

EPAs are defined as units of a professional activity requiring adequate knowledge, skills, and attitudes, with a recognized output of professional labor, independently executable within a time frame, observable and measurable in its process and outcome, and reflecting one or more competencies (ten Cate et al. 2015). The fundamental importance of EPAs lies in their ability to address the challenge that “competencies and intended learning outcomes may not be easily communicated and interpreted among the different stakeholders” and that “the application of competency descriptions in training may detract attention from the students’ performance on actual patient care” (Ellström et al. 2023). In the specialized field of Orofacial Pain (OFP), the development of nine specific EPAs represents a groundbreaking approach to measuring resident competency through innovative online assessment methodologies.

Understanding EPAs: They Are More Than Just Competencies

It’s crucial to understand that EPAs can be used as competency statements, but they are not only competencies. Instead, they are a way to translate the broad concept of competency into everyday practice (American Board of Surgery 2022). As outlined by ten Cate, EPAs are “tasks or responsibilities that can be entrusted to a trainee once sufficient, specific competence is reached to allow for unsupervised execution” and are now being defined in various health care domains (ten Cate et al. 2015). The fundamental difference lies in their practical application: while competencies describe what a clinician should be able to do, EPAs describe what they actually do in practice.

EPAs are units of professional practice that can be fully entrusted to an individual, once they have demonstrated the necessary competence to execute them unsupervised (ten Cate & Taylor 2021, ten Cate & Scheele 2022). The relationship between EPAs and competencies can be conceptualized as two separate dimensions, where EPAs represent the activities performed, while competencies represent the capabilities of the individuals performing them.

Like what you’re learning? Download a brochure for our Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine certificate or master’s degree program.

The Nine Orofacial Pain EPA-based Competencies

Our Orofacial Pain hybrid-online residency program developed nine distinct EPA/Competencies that comprehensively assess resident ability across all critical domains of practice. These EPAs align with Miller’s pyramid of clinical competence, which proposes four hierarchical levels: “knows” (knowledge), “knows how” (competence), “shows how” (performance), and “does” (action) (Miller 1990). The comprehensive nature of these EPAs ensures assessment across multiple levels of this established framework.

EPA 1: Basic Science Knowledge – Connecting Science to Practice

The Basic Science Knowledge EPA evaluates how effectively residents connect presenting symptoms to underlying neurobiological, pharmacological, and pathologic concepts. This EPA recognizes that every disease has a mechanism, and understanding these mechanisms is critical for clinicians who seek to treat complex orofacial pain conditions. The assessment moves beyond rote memorization to evaluate applied understanding in clinical contexts, requiring residents to select correct underlying etiology and mechanisms from eleven primary categories including biomechanical and structural mechanisms, muscular mechanisms, neurological mechanisms, inflammatory and immunological mechanisms, vascular mechanisms, and psychosocial and stress-related mechanisms.

Using our AI-Virtual Patient systems, residents must demonstrate their ability to integrate basic science knowledge with clinical case presentation. When students can’t identify the most logical neurobiological mechanisms behind a patient’s disease, they don’t really understand the disease’s science. This EPA also evaluates residents’ ability to explain how comorbid psychological conditions might be influencing pain presentation, requiring a sophisticated understanding of biopsychosocial pain models.

EPA 2: History Taking & Clinical Examination Skills – Clinical Reasoning in Action

Virtual patients are interactive digital simulations of clinical scenarios for the purpose of health professions education, and there is substantial evidence supporting their effectiveness (Kononowicz et al. 2019). The History Taking & Clinical Examination Skills EPA leverages this technology to assess clinical reasoning abilities through comprehensive evaluation of interview techniques and the physical examination choices made.

The AI-Virtual Patient system tracks which questions residents ask and compares these against expert-recommended lines of inquiry. The system evaluates whether residents identify psychosocial factors contributing to temporomandibular disorders, recognize “red flags” suggesting serious underlying pathology, and demonstrate appropriate clinical reasoning based on information received. A detailed quality heat map provides feedback on question quality, categorizing inquiries as “Excellent,” “Good,” “Fair,” or “Poor” based on their relevance to diagnostic reasoning.

This EPA addresses a critical educational need, as clinical reasoning analysis reveals significant variation in question quality and relevance. For example, questions about chief complaint, timeline/onset, and pain quality consistently receive “Excellent” ratings, while questions about headache frequency or occlusal appliance use may receive “Poor” ratings due to their lack of relevance to neuropathic pain presentations. This systematic feedback helps residents develop more effective interviewing skills that focus on clinically relevant information gathering.

EPA 3: Differential Diagnosis Skills – Comprehensive Diagnostic Reasoning

The Differential Diagnosis EPA assesses residents’ clinical reasoning ability through their consideration of appropriate alternative diagnoses beyond their primary suspicion. This EPA recognizes that when patients present with unilateral facial pain, residents must distinguish between conditions such as trigeminal neuralgia, temporomandibular disorders, atypical odontalgia, cancer-induced neuropathy, and burning mouth syndrome.

The system compares residents’ diagnostic considerations against expert assessments, providing targeted feedback on overlooked possibilities. Scoring is based on evidence support for each diagnosis, with correct choices receiving positive points and incorrect choices receiving negative points based on the adequacy of clinical history or examination evidence. For instance, a diagnosis of “Cancer Induced Neuropathy” might receive 10 points as the primary diagnosis in a case with adequate supporting evidence, while “Trigeminal Neuralgia” might receive -2 points due to inadequate clinical support.

This EPA ensures that residents develop comprehensive diagnostic reasoning skills that consider multiple possibilities rather than anchoring on a single diagnosis. The systematic comparison with expert assessments helps residents understand the clinical reasoning process and improves their ability to generate appropriate differential diagnoses.

EPA 4: Treatment Planning Skills – Evidence-Based Therapeutic Decision Making

The entrustable professional activities (EPAs) framework is one approach to assessment in a competency-based education model, as EPAs are observable, holistic activities that require the integration of knowledge, skills, and attitudes across competency domains (Hatala et al. 2015). The Treatment Planning Skills EPA evaluates whether residents can formulate comprehensive, evidence-based treatment approaches that appropriately balance pharmacological and physical modality interventions with behavioral strategies.

Assessment focuses on whether residents consider both efficacy and potential side effects when recommending medications, integrate patient education and self-management strategies into their plans, and select appropriate first, second, and third-line treatments. The system evaluates residents’ ability to develop treatment plans that address the multifaceted nature of orofacial pain, requiring integration of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Residents must demonstrate understanding of treatment hierarchies, selecting appropriate first-line treatments such as patient education and self-management, followed by second-line interventions like medications or physical therapy, and third-line approaches such as more invasive procedures or specialized referrals. The AI compares their treatment selections against expert recommendations, highlighting both appropriate choices and missed opportunities for comprehensive care.

EPA 5: Documentation Skills – Professional Communication and Record Keeping

Portfolios are advantageous in that they are able to test areas difficult to assess such as professionalism, continuous professional development, attitudes and critical thinking (Driessen et al. 2007). The Documentation EPA uses student-generated portfolio cases to assess documentation and communication skills, recognizing that effective communication with other healthcare providers is essential for quality patient care.

The QNOTE (Quality of Note Evaluation) framework evaluates documentation across multiple dimensions: whether notes are clear and understandable to clinicians, complete and address the clinical issue, concise and focused, current and up-to-date, organized and properly grouped, prioritized by order of clinical importance, and contain sufficient information for clinical decision-making. Every clinical note must include essential components such as chief complaint, history of present illness, additional disease-specific questions, past and current medical history, medication list, allergy history, social and family history, review of systems, examination findings, diagnosis/assessment, plan of action, actions taken, and follow-up notes.

This EPA ensures that residents develop the communication skills necessary to effectively document patient encounters and communicate with other healthcare providers. The systematic evaluation of documentation quality helps residents understand the importance of clear, comprehensive, and well-organized clinical notes in providing continuity of care.

EPA 6: Diagnostic Testing Skills – Appropriate Use of Advanced Diagnostics

The Diagnostic Testing EPA assesses residents’ ability to correctly select and interpret advanced diagnostic procedures. This EPA recognizes that appropriate use of diagnostic testing requires understanding not only what tests to order, but also how to interpret results and when testing is indicated or contraindicated.

The AI evaluates whether residents select appropriate tests for specific clinical scenarios, interpret results to confirm or modify initial clinical impressions, appropriately request imaging for conditions like limited mouth opening, and correctly interpret findings from MRIs or CT scans to distinguish between different pathologies such as disc displacement and degenerative joint disease. The system provides comprehensive feedback on diagnostic reasoning, helping residents understand the rationale for specific testing decisions.

Residents must demonstrate understanding of the diagnostic categories available, including imaging choices, dental disease testing, diagnostic injection/topical procedures, serologic testing, joint mobility testing, and specialized assessments like polysomnographic testing or biopsy procedures. The evaluation includes assessment of whether residents recognize when no additional diagnostic tests are needed, avoiding unnecessary testing while ensuring appropriate workup of complex cases.

EPA 7: Treatment Skills – Hands-On Clinical Competence

An objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) is an approach to the assessment of clinical competence in which the components are assessed in a planned or structured way with attention being paid to the objectivity of the examination (Harden et al. 1975). The Treatment Skills EPA requires in-person observation through thirty structured OSCEs conducted during intensive boot camp training sessions.

The OSCE is a versatile multipurpose evaluative tool that can be utilized to assess health care professionals in a clinical setting, assessing competency based on objective testing through direct observation (Zayyan 2011). These OSCEs evaluate technical skills including trigger point injections, joint mobilization, oral appliance therapy, comprehensive head and neck examination, and various diagnostic and therapeutic procedures outlined in the comprehensive Clinical Skills Manual for Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine.

All OSCE tests are recorded using dual-camera systems with synchronized audio feeds, allowing for detailed competency assessment using pre-established metrics. The recording system includes two panning and zooming cameras providing both resident and patient perspectives, along with two audio feeds using lavalier microphones to capture all verbal interactions. This comprehensive documentation allows for detailed review and assessment of both technical skills and communication abilities during clinical procedures.

The boot camp training provides hands-on experience with advanced clinical procedures that residents will be expected to perform independently in practice. The OSCE format ensures standardized assessment across all residents, providing objective evaluation of clinical competence that can be used for both formative feedback and summative assessment decisions.

EPA 8: Collaboration Skills – Interdisciplinary Care and Referral Management

The Collaboration EPA assesses whether residents appropriately identify situations requiring referral to specialists such as neurologists, rheumatologists, oncologists, or sleep medicine physicians. This EPA recognizes that effective patient care often requires collaboration with multiple healthcare providers, and residents must understand when such collaboration is necessary.

Using both AI-Virtual Patients and portfolio cases, the assessment evaluates whether residents recognize the need for collaborative management when patients present with symptoms suggesting systemic conditions like autoimmune disorders or neurological diseases. The system evaluates residents’ ability to select appropriate specialists, provide clear rationales for referrals, and understand the roles of different healthcare providers in comprehensive patient care.

For example, in cases involving suspected malignancy, residents must demonstrate understanding that referral to a head and neck oncologist would be most appropriate, while recognizing that the oncologist will coordinate with other specialists as needed. The assessment includes evaluation of whether residents understand the limitations of their own scope of practice and the importance of seeking appropriate consultation when cases exceed their competency level.

EPA 9: Evidence-Based Practice Knowledge – Integration of Research into Clinical Practice

Competency-based education has become central to the training and assessment of postgraduate medical trainees, with a strong focus on outcomes and professional performance (Holmboe et al. 2010). The Evidence-Based Practice Knowledge EPA uses portfolio and capstone project defenses to assess residents’ ability to integrate current scientific evidence into clinical decision-making.

Assessment criteria include accurate reflection of evidence strength when presenting treatment options, ability to distinguish between established approaches and emerging therapies with limited validation, and integration of academic rigor into clinical practice through research projects. Residents must demonstrate their capacity to critically evaluate research literature, understand study limitations, and appropriately apply research findings to clinical decision-making.

The capstone project defense represents the culmination of residents’ research training, requiring them to conduct original research that contributes to the understanding of orofacial pain conditions or treatment approaches. The portfolio defense evaluates residents’ ability to synthesize evidence across multiple cases, demonstrating how research findings inform their clinical reasoning and treatment decisions.

Assessment Integration and Scoring

Because our students are hybrid-online residents we elected to use a combination of virtual patient testing, portfolio and capstone defense as our summative examinations. This comprehensive assessment system integrates multiple data sources to provide a holistic competency evaluation. Each EPA is scored based on resident performance across relevant assessment modalities, with scores ranging from detailed point-based systems for specific choices to global competency ratings. The integration of multiple assessment methods provides a more robust evaluation of resident competency than any single assessment approach could achieve.

The system generates comprehensive competency profiles showing resident performance across all nine EPAs, with visual representations highlighting strengths and areas for improvement. This approach allows for individualized feedback and development planning, supporting the competency-based education model’s emphasis on learner-centered assessment and variable time to competency achievement.

The assessment framework recognizes that competency development is not uniform across all domains, and residents may demonstrate readiness for entrustment in some EPAs before others. This flexible approach supports individualized learning pathways while ensuring that all residents achieve the required competencies before graduation.

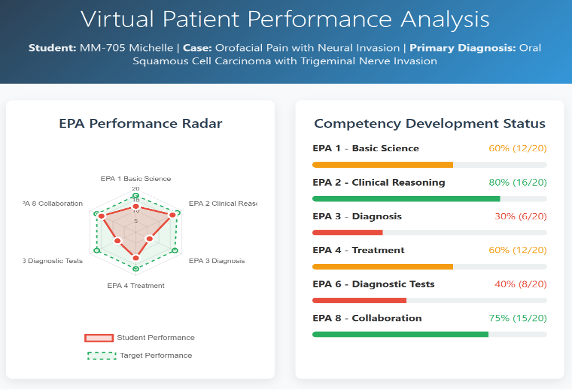

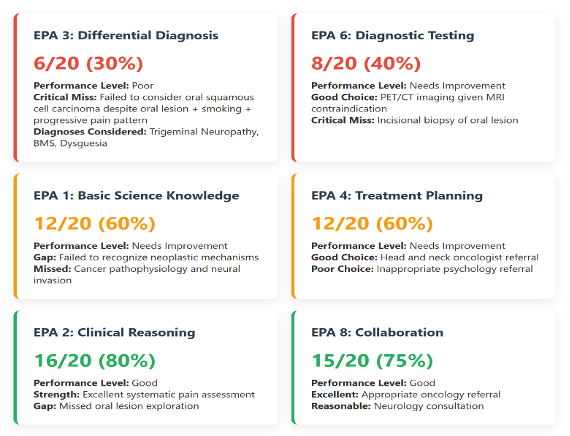

Figure 1 and 2 below: This a mock up of a student’s Performance Analysis that is generated at the end of their Virtual Patient attempt. It shows a radar map of the student’s performance on the 6 EPA domains that the VP assess. It is available almost instantaneously at the end of the VP test or practice VP attempt.

Conclusion: Competency Equals Graduation Readiness

In summary, the nine Orofacial Pain EPAs represent a sophisticated and comprehensive approach to measuring resident competency in specialized medical training. By integrating innovative technologies with established assessment methodologies, this framework provides a model for competency-based education that other specialties can adapt and implement.

The Orofacial Pain EPA framework described herein demonstrates that with careful design and implementation, competency-based medical education can effectively prepare residents for the challenges of modern clinical practice in Orofacial Pain while maintaining the highest standards of patient safety and care quality.

Earn an Online Postgraduate Degree in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine

Are you interested in a variety of issues focused on orofacial pain, medicine and sleep disorders? Consider enrolling in the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC’s online, competency-based certificate or master’s program in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine.

References

American Board of Surgery. (2022). Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs). American Board of Surgery. Retrieved from https://www.absurgery.org/get-certified/epas/

Carraccio, C., Wolfsthal, S. D., Englander, R., Ferentz, K., & Martin, C. (2002). Shifting paradigms: from Flexner to competencies. Academic Medicine, 77(5), 361-367.

Driessen, E., van Tartwijk, J., van der Vleuten, C., & Wass, V. (2007). Portfolios in medical education: why do they meet with mixed success? A systematic review. Medical Education, 41(12), 1224-1233.

Harden, R. M., Stevenson, M., Downie, W. W., & Wilson, G. M. (1975). Assessment of clinical competence using objective structured examination. British Medical Journal, 1(5955), 447-451.

Holmboe, E. S., Sherbino, J., Long, D. M., Swing, S. R., & Frank, J. R. (2010). The role of assessment in competency-based medical education. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 676-682.

Kononowicz, A. A., Woodham, L. A., Edelbring, S., Stathakarou, N., Davies, D., Saxena, N., & Zary, N. (2019). Virtual patient simulations in health professions education: systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(7), e14676.

Miller, G. E. (1990). The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine, 65(9), S63-S67.

ten Cate, O. (2005). Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Medical Education, 39(12), 1176-1177.

ten Cate, O., Chen, H. C., Hoff, R. G., Peters, H., Bok, H. G. J., & van der Schaaf, M. F. (2015). Curriculum development for the workplace using Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs): AMEE Guide No. 99. Medical Teacher, 37(11), 983-1002.

ten Cate, O., & Taylor, D. R. (2021). The recommended description of an entrustable professional activity: AMEE Guide No. 140. Medical Teacher, 43(10), 1106-1114.

Zayyan, M. (2011). Objective structured clinical examination: the assessment of choice. Oman Medical Journal, 26(4), 219-222.