Introduction

Headaches are among the most common neurological complaints worldwide, affecting more than half of the population at some point in their lives. In the United States, the age-adjusted prevalence of migraine and severe headache is approximately 15.9%, with a disproportionate impact on women and individuals of lower socioeconomic status [1]. While neurologists or primary care providers typically manage these disorders, properly trained dentists can recognize and triage patients who present with orofacial symptoms, contributing significantly to earlier diagnosis and more effective management of headache-related conditions.

Why Headaches Matter in Dentistry

Headache symptoms frequently overlap with orofacial pain complaints, often presenting as jaw discomfort, facial pressure, or temple pain. Since these regions are routinely examined during head and neck evaluations in dental visits, patients often present to their dentist with symptoms they attribute to dental causes. However, conditions such as temporomandibular disorders (TMD), sleep-disordered breathing, lifestyle factors, and medication overuse can mimic or contribute to primary headache disorders like migraines and tension-type headaches. Given the trigeminal system’s involvement in both dental and headache-related pain pathways, dentists are uniquely positioned to assess overlapping craniofacial pain conditions.

Headache Classifications and Dental Relevance

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) divides headaches into primary disorders (migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache) and secondary headaches caused by underlying conditions.

Primary Headaches

Primary headache disorders exhibit significant epidemiological patterns relevant to dental practice:

- Migraine manifests as pulsatile, often unilateral pain accompanied by nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia, affecting 11% to 15.9% of adults with a pronounced female predominance, particularly during reproductive years [1, 2].

- Tension-type headache represents the most common headache subtype worldwide, with lifetime prevalence reaching 40% [2]. The pediatric population shows remarkably high rates, with primary headaches affecting up to 62% of children and adolescents, migraine occurring in 11% and tension-type headache in 17% of this age group [6].

Secondary Headaches

Secondary headaches develop as symptoms of underlying disorders that are known to cause headaches. For dental professionals, several categories of secondary headaches are particularly relevant due to their overlap with orofacial pain conditions. Understanding these clinical intersections enables dentists to provide valuable contributions to interdisciplinary diagnosis and collaborative patient care.

Like what you’re learning? Download a brochure for our Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine certificate or master’s degree program.

Headache Attributed to Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD)

Multiple studies confirm a strong association between painful TMDs and primary headaches, especially migraines and tension-type headaches. A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that the odds of migraine in individuals with painful TMD were between 4.14 and 5.44 times higher compared to controls [7]. Similarly, chronic headache was significantly associated with TMD, with odds ratios ranging as high as 95.93. Mixed TMDs, involving both muscular and articular components, were found to moderately correlate with both migraines and episodic tension-type headaches [4]. While causality has not been firmly established, treating TMDs in patients with comorbid headaches may reduce headache frequency and intensity.

Headache Attributed to Sleep-Disordered Breathing

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) represents another condition that significantly overlaps with headache disorders. A 2024 systematic review found that the pooled prevalence of all headaches in patients with OSA was 33%, including 19% for tension-type headaches and 16% for migraine [3]. While the relative risk of headache in OSA patients was modest (RR = 1.43), the burden of morning headaches and their impact on quality of life were notable findings that dental providers should recognize.

Lifestyle and Systemic Comorbidities

Alcohol is commonly cited as a headache trigger, particularly for migraines, though recent meta-analyses reveal that migraine sufferers actually report lower alcohol intake than the general population (RR = 0.71), likely due to conscious trigger avoidance rather than protective effects. Red wine remains a potent trigger even in small amounts, possibly due to histamine content. Documenting alcohol intake remains clinically valuable, especially in patients with facial pain or frequent analgesic use.

Headache frequency generally decreases with age, though this may be influenced by cognitive function. In a cohort of over 450 individuals, headache prevalence remained steady across cognitive groups (22.8-27.1%), but headache days declined with age regardless of cognitive status, with age being the only significant predictor [5].

Headache patterns vary significantly across the lifespan and by sex. While prevalence remains balanced between boys and girls before puberty, rates rise sharply in adolescent females, suggesting hormonal influences. In children and adolescents, primary headaches affect 62% overall, with migraine at 11% and tension-type headaches at 17%, predominantly affecting post-adolescent females. These conditions significantly impact academic performance, social functioning, and caregiver productivity, yet remain underdiagnosed and undertreated, highlighting the need for age- and sex-specific screening strategies in both medical and dental settings [6].

Medication Overuse Headache (MOH)

Medication overuse headache is a secondary headache disorder that arises from the frequent use of acute headache medications, including triptans, analgesics, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). It affects approximately 1% to 2% of the general population and up to 30% of patients referred to headache specialty clinics. MOH typically develops in individuals with an underlying primary headache disorder, such as migraine or tension-type headache, and may lead to chronic daily headaches and reduced treatment responsiveness.

Socioeconomic factors, including lower levels of education, income, and insurance status, have been associated with increased risk and poorer access to appropriate treatment. A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that structured medication withdrawal, combined with preventive therapies and patient education, significantly improves outcomes in patients with MOH [8].

Dental providers should remain vigilant when reviewing medication histories, particularly in patients reporting frequent use of over-the-counter pain medications for facial or jaw discomfort. Early identification of possible MOH can prompt timely medical referrals and support more effective headache management strategies.

The Dentist’s Role in Clinical Screening

The importance of dental providers in identifying and referring patients with overlapping headache and orofacial pain has been emphasized in multiple interdisciplinary guidelines. Romero-Reyes and Uyanik highlighted the essential role of dentists in managing orofacial pain conditions that present as or coexist with headaches [9]. Similarly, the Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD), developed by Schiffman et al., provides a standardized clinical framework for identifying and categorizing TMD and associated conditions such as tension-type headaches and myofascial pain [10]. These protocols, validated for both clinical and research use, emphasize muscle and joint palpation, medical history intake, and pain-related disability assessment as key steps in screening for overlapping headache syndromes.

Dentists who are properly trained in recognizing headache red flags, performing structured orofacial examinations, and collaborating with medical colleagues can significantly improve diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes.

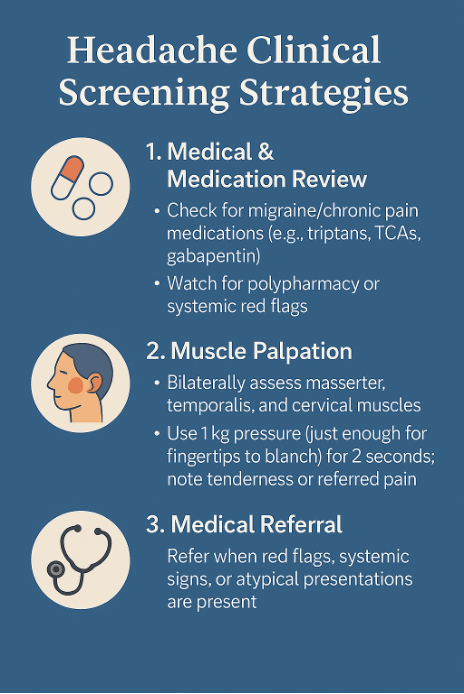

Key Clinical Screening Strategies (Figure 1 & Figure 2)

Comprehensive Medical History and Medication Review:

- Screen for medications associated with migraine management (e.g., triptans, beta-blockers) and chronic pain (e.g., TCAs, gabapentin)

- Identify polypharmacy red flags that may point to underlying neurologic, psychiatric, or systemic comorbidities

Physical Examination Protocol:

- Perform standardized bilateral palpation of the masticatory muscles (primarily masseter and temporalis) and cervical muscles using 1 kg of pressure for 2 seconds

- Note tenderness, referred pain, or asymmetry, and recognize the familiarity of pain sensation during the examination

- The pressure should be just enough to blanch the fingertips

Medical Referral Indicators:

Refer for medical evaluation when red flags are present, including atypical presentations, new onset at older age or during pregnancy, or when systemic signs are identified [11]

Figure 1: Clinical decision-making flowchart for headache evaluation in dental practice. This guide helps dentists systematically assess patients presenting with head and neck pain, incorporating headache classification principles and referral criteria to optimize patient care and treatment outcomes.

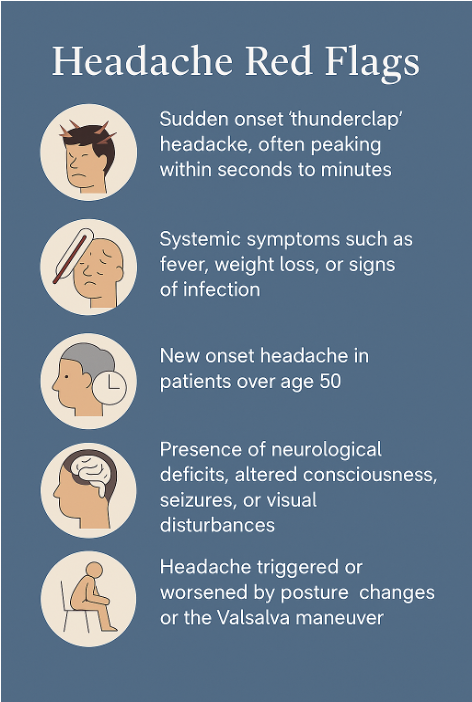

Figure 2: Red flag warning signs for secondary headaches requiring immediate medical referral. The SNNOOP10 criteria help dental practitioners identify serious underlying conditions that may present as headache or orofacial pain, emphasizing the importance of systematic screening and timely interdisciplinary collaboration.

Conclusion

As our understanding of headache disorders continues to evolve, the role of general and orofacial pain specialist dentists must expand accordingly. Rather than serving solely as evaluators of dental pathology, dentists are increasingly recognized as frontline healthcare providers capable of identifying complex pain patterns involving the head and neck. Headache presentations that mimic or overlap with orofacial pain demand a broader clinical perspective—one that integrates neurological insight, interdisciplinary coordination, and structured screening protocols.

The evidence presented underscores the importance of recognizing shared pathophysiological mechanisms, conducting thorough medication reviews, and identifying red flags that indicate systemic or neurological disease. By adopting a more comprehensive approach to craniofacial pain assessment, dental professionals can contribute not only to the relief of local symptoms but also to the early detection and improved management of debilitating headache disorders. This evolution in practice not only enhances patient outcomes but also elevates the standard of care delivered in contemporary dentistry.

Earn an Online Postgraduate Degree in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine

Are you interested in a variety of issues focused on orofacial pain, medicine and sleep disorders? Consider enrolling in the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC’s online, competency-based certificate or master’s program in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine.

References

[1] Burch R., Rizzoli P., & Loder E. (2021). The prevalence and impact of migraine and severe headache in the United States. Headache, 61(1), 60–68.

[2] Blaszczyk B. et al. (2023). Relationship between alcohol and primary headaches: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 24:116.

[3] Blaszczyk B. et al. (2024). Prevalence of headaches and their relationship with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 73, 101889.

[4] Dibello V. et al. (2023). Temporomandibular Disorders as Contributors to Primary Headaches: A Systematic Review. Journal of Oral & Facial Pain and Headache, 37(2), 91-100.

[5] Echiverri K. et al. (2018). Age-Related Changes in Headache Days Across the Cognitive Spectrum. Pain Medicine, 19(7), 1478–1484.

[6] Onofri A. et al. (2023). Primary headache epidemiology in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 24:8.

[7] Reus J.C. et al. (2022). Association between primary headaches and temporomandibular disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Dental Association, 153(2), 120-131.

[8] de Goffau, M. J., Klaver, A. R. E., Willemsen, M. G., Bindels, P. J. E., & Verhagen, A. P. (2017). The Effectiveness of Treatments for Patients With Medication Overuse Headache: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The journal of pain, 18(6), 615–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2016.12.005

[9] Romero-Reyes, M., & Uyanik, J. M. (2014). Orofacial pain management: current perspectives. Journal of pain research, 7, 99–115. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S37593

[10] Schiffman, E., Ohrbach, R., Truelove, E., Look, J., Anderson, G., Goulet, J. P., List, T., Svensson, P., Gonzalez, Y., Lobbezoo, F., Michelotti, A., Brooks, S. L., Ceusters, W., Drangsholt, M., Ettlin, D., Gaul, C., Goldberg, L. J., Haythornthwaite, J. A., Hollender, L., Jensen, R., … Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group, International Association for the Study of Pain (2014). Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group†. Journal of oral & facial pain and headache, 28(1), 6–27. https://doi.org/10.11607/jop.1151

[11] Tassorelli C., Jensen R.H., Allena M., De Icco R., De Fiore L., Bendtsen L., et al. (2021). Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice: SNNOOP10 list. Consensus statement from the European Headache Federation. Journal of Headache and Pain, 22, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01221-9