Erythema multiforme (EM): First described in 1866 by Ferdinand von Hebra as an acute, self-limited cutaneous disease characterized by multiform skin lesions, now called EM minor [1]. In 1950, Bernard A. Thomas classified EM into erythema multiforme minor (von Hebra) and erythema multiforme major characterized by erosions or ulcerations involving the oral, genital, and/or ocular mucosae lesions accompanied by skin lesion seen in EM minor.

In addition to the mucosal involvement, a key difference between these two subtypes is systemic symptoms such as fever and arthralgia preceding and/or accompanying EM major.

The similarities in clinical and histopathologic findings between Erythema Multiforme Major and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) have led to controversy over the distinction between these two mucocutaneous conditions. Historically, SJS and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) are considered a disease continuum of EM. In 1993 and 1995, Bastuji-Garin and colleagues proposed a new clinical classification for EM, SJS, and TEN supporting that SJS and TEN are distinct conditions from EM [2, 3].

However, it is still firmly believed that SJS and TEN are a disease continuum. The term “erythema multiforme” should not be used to refer to SJS/TEN or vice versa. The validity of the Bastuji-Garin classification was later confirmed by a large epidemiological study [4]. Regardless of all these classifications efforts, in an analysis of 37 published cases of drug-induced EM, 24 case reports (65%) did not meet clinical criteria for EM. [5].

Bastuji-Garin, S., et al. classified EM, SJS, and TEN into five categories [3]:

- EM, detachment below 10% of the BSA plus localized typical targets or raised atypical targets.

- SJS, detachment below 10% of the BSA plus widespread macules or flat atypical targets.

- Overlap SJS-TEN, detachment between 10% and 30% of the BSA plus widespread macules or flat atypical targets.

- TEN with spots* with or without blisters, detachment above 30% of the BSA plus widespread macules or flat atypical targets.

- TEN without spots*, detachment above 10% of the BSA with large epidermal sheets and without any macule or target.

Spot*: EM-Likes skin lesions

Etiology: EM etiology is divided into two main groups, infection and medication:

- Infections: There is strong evidence that EM is precipitated by infection (viral, bacterial, or fungal) in most cases. The most common inciting pathogen is Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV). This link between EM and HSV is evident by (i) developing EM a few weeks after an HSV infection, (ii) seropositivity for HSV antibody, and (iii) identify HSV antigen in EM patients. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection is an important etiology to be considered for EM in children. Malignancy, autoimmune disease, sarcoidosis, menstruation, and radiation have also been reported in rare cases. With the current COVID pandemic, oral health providers need to recognize that EM-like lesions have also been observed in association with COVID-19 infection and after COVID-19 vaccination [6].

- Medications: It is important to understand that less than 10% of EM cases are triggered by medication such as NSAIDs, antibiotics, anticonvulsants such as Carbamazepine, and others. Medication-induced EM has contributed to the nosology controversy of EM and SJS/TEN, which is almost caused by medications. Looking carefully at the EM patient’s new medication and if there is a temporal relationship is key in identifying drug-induced EM. Identifying the offending drug is crucial in the treatment and improve the prognosis of EM. Exposure to the offending drug commonly precedes the onset of symptoms by one to four weeks, but re-exposure may result in the onset of symptoms in as little as 48 hours.

Pathogenesis

The suggested pathogenesis for HSV induces EM CD34+ cells to carry fragments of HSV DNA to the skin and mucosa where it incites a T cell‐type hypersensitivity reaction that generates interferon-γ, with the amplified immune system recruiting more T cells initiate acute inflammation causing the eruption of the EM lesions [7].

EM Clinical Findings

The clinical course of EM varies depending on the cause. EM caused by infection is usually self-limited, resolving within a few weeks. In a minority of cases, the disease recurs over the years. Studies show that recurrent EM is mainly associated with recurrent HSV infections, which might happen two to three weeks before the EM clinical symptoms appear. As mentioned above, although less common, recurrence might happen when reexposed to an offending medication.

Regardless of the cause, EM lesions erupt within a few weeks from the infection or taking the offending medication. Skin and oral lesions appear rapidly over a few days and begin as red macules that become papular in the skin, starting primarily in the hands and moving centripetally toward the trunk in a symmetrical distribution. This acute onset of the mucocutaneous lesions is one of the hallmarks of considering EM in the differential diagnosis.

In EM Major, it is not uncommon to have a prodrome of fever, arthralgias, malaise, headache proceeding or accompany the mucocutaneous lesions. In M. pneumoniae infection-associated EM, sore throat, rhinorrhea, and cough might be seen. Although not very common, skin lesions in EM Major might present with an epidermal detachment; if the skin detachment is more than 10% of body surface area (BSA), SJS/TEN should be considered. Hence the name multiforme, skin lesions have multiple forms. The morphology of EM lesions may vary between patients and may also evolve throughout the disease stage (Early Vs. Late) in a single patient [3]:

- Target lesion: The stander skin lesions for EM are defined as individual lesions less than 3 cm in diameter with a regular round shape, well-defined border, and at least three different zones.

- Raised atypical targets: Defined as round, edematous, palpable lesions, with only two zones and/or a poorly defined border.

Interestingly, skin lesions are mostly asymptomatic; however, some patients will complain of itching or burning sensation.

Like what you’re learning? Download a brochure for our online, postgraduate Oral Pathology and Radiology certificate program.

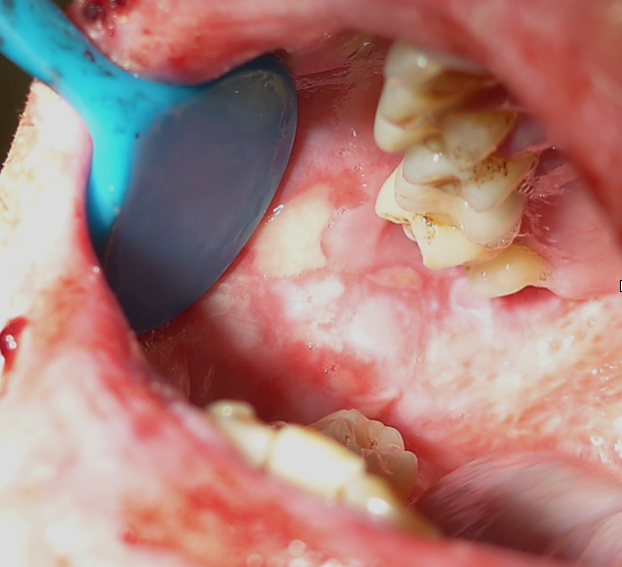

The intraoral lesion is mainly seen in EM major, not minor. The lesions range from mild erythema and erosion to large painful ulcerations covered by a yellow-white fibrinous exudate Figure 1. Lip inflammation, ulceration, and crusting are very common in patients with EM major Figure 2. It is important to understand that these lesions are not exclusive to EM and can be seen in SJS/TEN, and other conditions include Paraneoplastic Pemphigoid.

EM Minor always presents with skin lesions similar to the major subtype described above but without epidermal detachment and without or only mild mucosal disease. Also, no associated systemic symptoms accompany EM minor.

Although not included in the Bastuji-Garin classification, oral health providers must realize that sometimes EM cases present with oral mucous membrane involvement only [8].

Laboratory findings: Clinical findings and course of the disease are usually enough to diagnose patients with EM. Laboratory tests such as CBC, CMP, and CRP are not specific. Histopathologically, basal layer liquefaction and inflammatory infiltrate (includes lymphocytes, histiocytes), spongiosis, and intracellular edema. Although these histopathological features are not specific, an oral biopsy could be performed with persistent EM to assist with the exclusion of other disorders or when the diagnosis of EM is questionable. Investigational tests can be done by infectious disease specialists when the infection is considered as a possible etiology.

Diagnosis of EM Major: Diagnosis of EM Major would be appropriate in a patient with the following clinical features [3, 4]:

- A history of recent infection strongly suggests EM. Although medications are associated with 10% of EM, medications are the leading cause of SJS/TEN.

- A prodrome of febrile illness and malaise can be seen in EM but not specific and can be seen more often in SJS/TEN.

- EM mostly does not have skin detachment and, if present, is it below 10% of the BSA. On the other hand, SJS/TEN is commonly associated with skin detachment. SJS is the less severe condition comparing to TEN, in which skin detachment is <10 percent of the BSA. TEN involves detachment of >30 percent of the BSA. When skin detachment is between 10 and 30 percent of BSA, it considers overlap SJS/TEN.

- EM is characterized by typical target-like or raised atypical targets lesions (described above). SJS/TEN lesions are commonly flat atypical targets defined as round lesions with only two zones and/or a poorly defined border, nonpalpable with the exception of a potential central blister. Also, SJS/TEN lesions might present as purpuric macules with or without blisters. In general, blisters often occur on all or part of the SJS/TEN lesions and are rare to be seen in EM. In rare instances, TEN occurred without any discrete atypical target lesions. These cases are classified as TEN without spots.

- While EM skin lesions are symmetrical, localized, start from the extremities, and could move centripetally, SJS and TEN are widespread, start from the neck, face, and upper torso, and can extend centrifugally.

- Finally, comparing to SJS/TEN, recurrences are more common with EM.

Management

- Review the medical history to identify the cause is crucial. If a drug is suspected, contact the prescriber physician after approval, discontinue the medication. If an infection is suspected, consider a consultation with the patient’s primary physician or infectious disease specialist for appropriate treatment of the infection.

- When skin is involved, always consider a dermatology consultation.

- The pharmacological management will depend on the severity and recurrence of the condition:

- Limited oral mucosal involvement: For alleviating the pain, a mouthwash containing equal parts of viscous lidocaine 2%, diphenhydramine (12.5 mg/5 mL), and aluminum hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide mixture (e.g., Maalox) as a swish-and-spit, can be used as needed, up to four times per day. Dexamethasone (0.5 mg/5 mL) oral elixir 4 times/day swish-and-spit can be used for diffused ulcers. If the ulcers are limited to a small area, fluocinonide 0.05% gel is applied two to three times per day.

- Extensive oral mucosal involvement: Severe oral mucous membrane involvement that prevents sufficient oral intake consider hospitalization. If hospitalization is not needed, In the first-line treatment is systemic glucocorticoids. Dosage and tapering will depend on the severity of the case and response to the treatment. Azathioprine and dapsone have been reported helpful in several cases.

- An antiviral suppersion therapy, such as Acyclovir 400mg twice a day, should be considered in recurrent EM associated with HSV.

All the above medications have contraindications which the clinician has to be aware of before prescription.

Figure 1: Intraoral erythema multiforme: Diffused ulcers covered by a yellow-white exudate/fibrinous surface. Image courtesy of Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine Center, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC.

Figure 2: Erythema multiforme with ulcerative, hemorrhagic crusts of the lips. Image courtesy of Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine Center, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC.

Postgraduate Oral Pathology and Radiology Certificate

Learn more about the clinical and didactic skills necessary to evaluate and manage patients with oral diseases by enrolling in Herman Ostrow School of USC’s online, competency-based certificate program in Oral Pathology and Radiology.

References

1. F., v.H., Atlas der Hautkrankheiten. Vienna, Austria: Kaiserliche Akademie der Wissenschaften.

2. Assier, H., et al., Erythema multiforme with mucous membrane involvement and Stevens-Johnson syndrome are clinically different disorders with distinct causes. Arch Dermatol, 1995. 131(5): p. 539-43.

3. Bastuji-Garin, S., et al., Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol, 1993. 129(1): p. 92-6.

4. Auquier-Dunant, A., et al., Correlations between clinical patterns and causes of erythema multiforme majus, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: results of an international prospective study. Arch Dermatol, 2002. 138(8): p. 1019-24.

5. Roujeau, J.C., Re-evaluation of ‘drug-induced’ erythema multiforme in the medical literature. Br J Dermatol, 2016. 175(3): p. 650-1.

6. McMahon, D.E., et al., Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: A registry-based study of 414 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2021. 85(1): p. 46-55.

7. Ono, F., et al., CD34+ cells in the peripheral blood transport herpes simplex virus DNA fragments to the skin of patients with erythema multiforme (HAEM). J Invest Dermatol, 2005. 124(6): p. 1215-24.

8. Bean, S.F. and R.K. Quezada, Recurrent oral erythema multiforme. Clinical experience with 11 patients. Jama, 1983. 249(20): p. 2810-2.