The promotion of oral health through education or consumer informational nudges [1] has been shown to effectively increase oral health awareness, encourage self-care hygiene techniques, and foster habits that support long-term oral health.

Oral health education is commonly delivered through oral or written communication, dental aids, digital tools, or demonstrations. Research shows that effective instruction can substantially improve patients’ knowledge about managing their oral health and maintaining healthy routines.

The goals of oral health education include building the patient’s capacity to maintain a healthy mouth with daily care habits for prevention, disease management, and reducing systemic complications. Health and disease are two contrary situations [2]; thus, all stakeholders in oral health education roles can be most impactful by implementing effective interventions that consider patients’ readiness. Oral health education strategies can be tailored to build on patients’ knowledge and motivation.

Oral care maintenance and management are unique because they require individuals to consistently demonstrate effective manual dexterity and compliance with home care routines and dental products. Therefore, motivation becomes a factor for educators to acknowledge. Additionally, an evaluation for discomfort or pain in the mouth that could inhibit motivation is always indicated.

Health practitioners often consider what will sustain or inhibit oral health maintenance behaviors over time, but assessing these factors is not always feasible. The expectancy-value theory (EVT) [2 ] suggests individuals are motivated by outcomes they value and believe they can achieve. Additionally, the salutogenic approach emphasizes the positive aspects of health situations and the patient’s use of available resources for achieving or maintaining healthy status. Both theories have direct applications and impact on oral health education and subsequent health decision-making [3].

Patients are often motivated to learn about their health conditions. Providing them with accurate, up-to-date, and consistent information can enhance their ability to manage their oral health effectively. Traditionally, oral health education efforts involve dentists, hygienists, dental assistants, social workers, healthcare providers, and global health organizations. An increase in the diverse range of well-informed healthcare providers and industry partners is needed. A collaborative approach can amplify the impact of education. Research supports that proper training in oral health education for current and emerging providers improves care access for communities, leading to stronger, more sustainable health outcomes [3], [4]. Furthermore, expanding training within the current dental workforce is recommended, as dental professionals are primary sources for implementing effective patient education strategies [5].

Applying the health belief model (HBM) [5] alongside expectancy-value theory (EVT) and positive health, approaches may help address perceived barriers, emphasize benefits, and build self-efficacy, all of which can increase adherence to recommended oral health practices [6]. And, it is necessary to acknowledge that individuals may not always be ready to process information, retain knowledge, and take action for their health [7].

All stakeholders providing oral education should attempt to find the patient’s ‘value’ in addition to their health beliefs and their available resources to maximize the impact of long-term dental health.

Like what you’re learning? Consider enrolling in the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC’s online, competency-based certificate or master’s program in Community Oral Health.

Suggestions

To advance oral health, the following is suggested: integrate oral health lessons into broader wellness curricula, develop oral health messages for the public, develop tailored oral health messages for target and vulnerable populations, and prepare health education scripts for quick and consistent oral and written communication in multiple languages, utilizing short, clear, unbiased language. Consider how visual aids, pictographs, or infographics can convey directions for health routines or dental products.

Make attempts to understand patients’ expectations and motivations for maintaining consistent oral health habits [8], then tailor interventions and educational strategies that align with motivation. Lastly, integrate value-based elements into education by getting to know the patient. All oral health educators and stakeholders are encouraged to become keenly concerned for the patient’s outcomes by engaging them (consider health literacy) in a straightforward, empathetic manner [9].

The Ideal Versus the Practical

Measuring the impact of oral health education can be complex, but its potential is significant, particularly in reducing dental diseases and improving overall health across populations, including groups with systemic health challenges linked to oral health [10], [11]. Keep in mind that psychosocial factors play an essential role in maintaining healthy oral habits beyond the direct influence of education. Precisely quantifying the impact of educational efforts may be challenging, but it is reasonable to operate under the assumption that education generally has a positive effect when well delivered.

The ultimate goal of delivering (oral) health education is to move beyond patient compliance to patient adherence, where patients feel confident [12] to consistently apply what they’ve learned to manage their health independently.

Assessing Value and Adherence with a Quick Chairside Tool

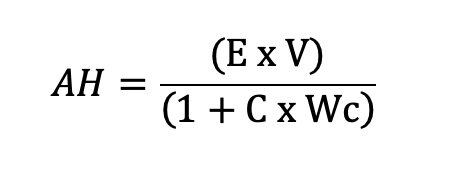

To evaluate the impact of oral health education using expectancy-value theory, consider using a simplified formula with values set as low (1), medium (2), or high (3) for each variable. This scaled, easy-to-use version allows practitioners to quickly assess an individual’s expectancy, value, and likelihood of adhering to oral health practices. Sharing this information with patients may help encourage their compliance, identify which factors need attention, and give some indication of the impact that education was effectively developed and delivered.

Figure 1.Health Adherence Expectancy-Value Formula (HAEVF)

The variables for expectancy, value, cost, and cost multiplier are scaled at 1 (low), 2 (medium), and 3 (high).

| E: Expectancy | Represents confidence or belief in the ability to perform oral health behaviors. | ||||

| V: Value | Reflects how much importance or benefit the individual places on the outcome (health benefits, appearance, etc.). | ||||

| C: Cost | Represents perceived barriers (time, financial cost, effort, discomfort) to maintaining oral health behaviors. | ||||

| Wc: Weight of the Cost | Reflects how important the individual perceives the cost | ||||

| AH value | E (expectancy) | V (value) | C (cost) | Wc (weight of cost) | AH Outcome |

| Highest | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4.5 |

| Lowest | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0.1 |

| (Adaptable) guiding questions following the delivery of (oral) health education: | |||||

| E: How confident are you in maintaining a consistent oral hygiene routine? (e.g., brushing and flossing as recommended) 1 (low), 2 (medium), and 3 (high) | |||||

| V: How important is maintaining good oral health? (e.g., preventing cavities, goal to preserve teeth for a lifetime, having a clean mouth) to you? 1 (low), 2 (medium), and 3 (high) | |||||

| C: How much of a barrier do you perceive the time, effort, or money required to maintain oral hygiene as being? 1 (low), 2 (medium), and 3 (high) | |||||

| Wc: How significant are these barriers (time, effort, cost) to you in your decision to maintain or not maintain your oral hygiene routine? 1 (low), 2 (medium), and 3 (high) | |||||

*The Health Adherence Expectancy-Value Formula (HAEVF) formula is original and, to the best of my knowledge, is the first to integrate the concepts of oral health education with expectancy-value theory proposed as a prototype chairside assessment tool for a quick and simple predictive analysis of adherence to delivered (oral) health education.

Earn an Online Postgraduate Degree in Community Oral Health

Do you like learning about a variety of issues while focused on the unique needs of community health dental programs? Consider enrolling in the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC’s online, competency-based certificate or master’s program in Community Oral Health.

References

[1] S. Mertens, M. Herberz, U. J. J. Hahnel, and T. Brosch, “The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – PNAS, vol. 119, no. 1, 2022, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107346118.

[2] S. Bhattacharya et al., “Salutogenesis: A bona fide guide towards health preservation,” Journal of family medicine and primary care, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 16–19, 2020, doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_260_19.

[3] F. Movaseghi Ardekani, F. Ghaderi, M. H. Kaveh, M. Nazari, and Z. Khoramaki, “The Effect of an Educational Intervention on Oral Health Literacy, Knowledge, and Behavior in Iranian Adolescents: A Theory-Based Randomized Controlled Trial,” BioMed research international, vol. 2022, pp. 5421799–10, 2022, doi: 10.1155/2022/5421799.

[4] E. M. Morón and R. Singer, “An interprofessional school‐based initiative to increase access to oral health care in underserved Florida counties,” Journal of public health dentistry, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 155–160, 2023, doi: 10.1111/jphd.12562.

[5] G. H., Gambôa, A., & Yusuf, H. (2022). The Impact of Oral Health Training on the Early Year’s Workforce Knowledge, Skills and Behaviours in Delivering Oral Health Advice: A Systematic Review. Community Dental Health, 39(4), 260–266.

[6] D. W. McNeil, “Behavioural and cognitive‐behavioural theories in oral health research: Current state and future directions,” Community dentistry and oral epidemiology, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 6–16, 2023, doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12840

[7] M. Saffari et al., “An Intervention Program Using the Health Belief Model to Modify Lifestyle in Coronary Heart Disease: Randomized Controlled Trial,” International journal of behavioral medicine, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 631–641, 2024, doi: 10.1007/s12529-023-10201-1.

[8] X.-H. Zhang, F. Xie, H.-L. Wee, J. Thumboo, and S.-C. Li, “Applying the Expectancy-Value Model to Understand Health Values,” Value in health, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. S61–S68, 2008, doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00368.x.

[9] P. B. Bhattad and L. Pacifico, “Empowering Patients: Promoting Patient Education and Health Literacy,” Curēus (Palo Alto, CA), vol. 14, no. 7, pp. e27336–e27336, 2022, doi: 10.7759/cureus.27336.

[10] L. Church, A. Spahr, S. Marschner, J. Wallace, C. Chow, and S. King, “Evaluating the impact of oral hygiene instruction and digital oral health education within cardiac rehabilitation clinics: A protocol for a novel, dual centre, parallel randomised controlled trial,” PloS one, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. e0306882-, 2024, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0306882.

[11] Z. H. Khoury, P. Illesca, and A. S. Sultan, “The role of primary care providers in oral health education for patients with diabetes,” Patient education and counseling, vol. 104, no. 6, pp. 1497–1499, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.020.

[12] E. Hickmann, P. Richter, and H. Schlieter, “All together now – patient engagement, patient empowerment, and associated terms in personal healthcare,” BMC health services research, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1–1116, 2022, doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08501-5.

[13] B. Nagengast, H. W. Marsh, L. F. Scalas, M. K. Xu, K.-T. Hau, and U. Trautwein, “Who Took the ‘×’ out of Expectancy-Value Theory? A Psychological Mystery, a Substantive-Methodological Synergy, and a Cross-National Generalization,” Psychological science, vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 1058–1066, 2011, doi: 10.1177/0956797611415540.