The management of dry mouth includes two aspects: attempts to affect a change in the causative factors of the condition; and, the prevention of any potential or worsening of existing consequences of dry mouth on oral health.

Diagnosis Directed Management

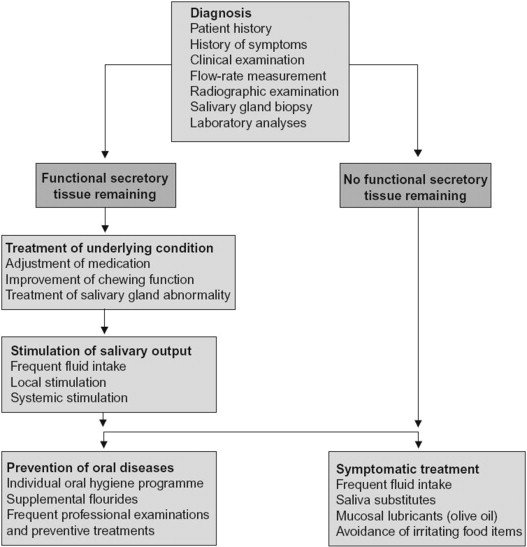

In order to determine where intervention may benefit, an accurate diagnosis of the cause and severity of dry mouth is the most important prerequisite for its treatment.

The diagnostic process should include a thorough history of the symptoms, the patient’s medication and medical history, a complete clinical examination with salivary flow rate measurements (both stimulated and unstimulated flow rates if possible), as well as imaging examinations, salivary gland biopsies and laboratory analysis when needed [63].

Subsequently, treatment can be directed at providing salivary substitutes and/or oral mucosal lubricants for palliation of the symptoms and/or to stimulation of salivary secretion from glandular tissue. The sequencing of this process is described by Närhi et al. [63].

Like what you’re learning? Download a brochure for our Geriatric Dentistry Master Program certificate or master’s degree program.

Modifiable Behaviors

An extensive list of the results of various investigations, including laboratory studies, imaging, biopsy and other measurement results for patients with prolonged dry mouth is reported elsewhere [58].

Temporary causes of dry mouth can be improved by avoiding or reducing intake of substances such as caffeine, alcohol or hot and spicy foods eaten. Other actions include the avoidance of mouth breathing and dehydration. Patients with long standing habits of smoking and alcohol usage may require the help of behavioral psychologists to wean them from the offending substance that is a causative or contributory factor to their dry mouth condition.

Medication Substitution or Dosing Changes

Medication induced salivary gland hypofunction is often a reversible condition and ceasing the drug therapy, reducing the number or dosage of medications or substituting the medication for a less xerogenic alternative may bring the salivary flow back to normal [25], [59], [63].

However, it is important to note that only a few studies compare the relative xerogenic potential of one drug to another and the knowledge on the relative effects of drugs to induce dry mouth is limited. So, such a substitution process has to be done by trial and error and the result may vary for each patient [59].

If the value of medical treatment outweighs any substitution or dosage adjustments, symptomatic treatments for dry mouth are indicated [25], [63]. In some cases, it may be possible to manage the dry mouth symptoms through optimal management of the underlying diseases such as better management of diabetes, Sjogren’s syndrome, sarcoidosis, or HIV.

Chronic Conditions

Management strategies for long-standing symptoms in patients with histories of head and neck radiation or systemic diseases with prolonged salivary gland hypofunction include a variety of topical and systemic management options [58].

Almost all cases of dry mouth will benefit from symptomatic therapy irrespective of etiology [63]. The goal is to moisten the oral mucosa.

Non-specific palliative management of dry mouth includes sipping water and sucking on ice chips frequently throughout the day to provide moisture [44], [58], [63].

For elderly patients, the use of water or ice chips should not be dependent on thirst sensations since satiety and thirst reflexes are obtunded in older age groups [72].

Water and glycerin in small spray bottles can also be useful for some patients for periodic relief of dry mouth during the day; and adding moisture to the environment at night with a room humidifier may give some relief during sleep.

Postgraduate Geriatric Dentistry

Are you looking for improved ways to diagnose, treat, and manage the oral healthcare of older patients? Explore our online master’s and certificate program in Geriatric Dentistry.

About the Author

The original article was authored in part by Dr. Roseann Mulligan, Director Geriatric Dentistry Master and Certificate programs at the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, and was originally published by Elsevier in the Journal of Prosthodontic Research.

References

[25] C. Scully

Drug effects on salivary glands: dry mouth

Oral Dis, 9 (2003), pp. 165-176

[44] T. Nederfors, R. Isaksson, H. Mornstad, C. Dahlof

Prevalence of perceived symptoms of dry mouth in an adult Swedish population – relation to age, sex and pharmacotherapy

Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol, 25 (1997), pp. 211-216

[58] S.R. Porter, C. Scully, A.M. Hegarty

An update of the etiology and management of xerostomia

Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 97 (2004), pp. 28-46

[59] Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co.

Search for drugs that may cause dry mouth

(2001, November)

[63] T.O. Närhi, J.H. Meurman, A. Ainamo

Xerostomia and hyposalivation: causes, consequences and treatment in the elderly

Drugs Aging, 15 (1999), pp. 103-116

[72] W.L. Kenney, P. Chiu

Influence of age on thirst and fluid intake

Med Sci Sports Exerc, 33 (2001), pp. 1524-1532